- Home

- Tristan Bancks

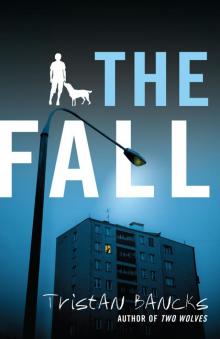

The Fall Page 5

The Fall Read online

Page 5

I was pretty much addicted to snooping. At home, I knew where Mum kept chocolate (on top of the pantry in a plastic tub with the medical supplies), Christmas presents (window seat, under the spare pillows) and my Xbox controllers (bottom cupboard, behind the rice cooker).

I grabbed the back of a dining chair and awkwardly dragged it across the floor into the bedroom, in front of the old timber wardrobe. The chair wobbled as I swung my good leg onto it. I took a deep breath and pushed up, grabbing the top of the wardrobe for balance. Magic licked my toes.

‘Stop!’ I whispered sharply but she didn’t listen.

I felt around the top of the wardrobe. I was close to the ceiling, which meant I was close to the floor of 6A. Is anyone up there right now? I wondered. Magic continued to lick between my toes.

I couldn’t see what was on top of the wardrobe but I ran my fingertips through inch-thick dust, searching for anything Harry may have hidden.

My thumb scraped something flat and metallic. My heart skipped as I pried the object off the timber. A key. A very dusty key. Not from Harry, though. This key had been here a long, long time and my father had only lived here a month or so. I sneezed, wiped the dust on my shorts and lowered myself off the chair. I felt the sting of my stitches pulling and the deep throb of the staples grinding against my bones. I sat on the floor and pressed myself flat to the timber so that I could look under the bed.

Nothing. Just more dust bunnies. Not as thick as on the wardrobe. They were more like dust rabbits up there.

I sat up and looked at the brassy-brown key. It had a serial number carved into it. It was a regular key, not an old one. I twisted around, placed my hands on the edge of the bed frame and pushed myself up. My arms were so sore. I kept my leg straight, grabbed my crutches and hobbled out to the kitchen bench, where the busted lock was sitting with a hunk of splintered timber still attached. I picked it up and tried the key but it wouldn’t fit.

I went to the windows, trying to protect my red-raw armpits from the tops of the crutches. The windows didn’t have locks. I couldn’t think of anything else in the apartment that did. The key was no good to me for now.

I wondered if any of my evidence or photos had anything to do with the crime that had been committed. Maybe none of it was useful.

I continued to search the apartment – through every drawer, inside every book, under every cushion and pillow and mattress. The only thing that seemed to be gone was the electricity bill that had fluttered to the floor when I grabbed Harry’s laptop off the dining table. This played on my mind. Maybe Harry had picked it up, taken it with him. Possibly. But what if the man had picked it up? He would have Harry Garner’s name linked to this address. I thought about messaging Harry but decided not to bother him. I didn’t want him getting annoyed with me. I would tell him after work.

I searched the medicine cabinet, the fridge and oven. The walls were lined with timber from floor to chest height, then there was a small ledge and plasterboard up to the ceiling. I tapped the timber part of the wall, hunting for some kind of secret cavity. The fire hose reel cupboard was set into the other side of this wall but it mustn’t have taken up the whole space because, over by Harry’s front door, the wall sounded hollow. I tried to get my fingertips in between the boards but they were all nailed in tightly – there was no way to check what was behind them.

I decided to make a note on my phone of all my father’s personal items:

1 toothbrush, green and white, cheap, bristles chewed and splayed

1 tube Macleans toothpaste, almost empty

1/2 packet of Quick-Eze indigestion tablets. Use-by date: 2/2/13

Fridge: rotten pear; empty pizza box; jar of chopped chilli

Cupboard: packet of Uncle Ben’s Instant Rice; tin of Heinz baked beans; tin of Edgell red kidney beans; Saxa picnic salt; an onion with a green stalk growing out of it

Wardrobe: 2 pairs of grey trousers; 2 white, long-sleeved button-up shirts (one with a pink stain on front); 6 pairs of underpants, all white-ish, two with holes near waistband at back; 1 pair of shoes

1 laptop and charger

1 hunting knife

I had to admit that the last one worried me. I found it in a very thin drawer at the bottom of the wardrobe between two larger drawers. Why does my father need a knife? He owned barely anything but he had this long, jagged knife with a black handle. Reporters in comics had guns. But my dad had a hunting knife. What was he hunting? Criminals?

What if he was involved in this crime? Is that how he knew something? Is that why he ignored me when I suggested going to the police?

I pushed the thought aside. It was stupid.

But was it? I hardly knew Harry, only a made-up, comic-book version of him. I met him six days ago and, before that, he was a fantasy to me. I had pictured calling him ‘Dad’ but instead he made me call him ‘Harry’. I imagined we’d have all these really big talks but, a lot of the time, he wasn’t even home. He had promised Mum that he would take the week off but he just kept working. ‘I haven’t had a day off in forty years,’ he told me. I believed him but I also thought that meeting his almost-thirteen-year-old son might be a good enough reason to have one. Sometimes it felt like he was avoiding me on purpose, like he didn’t know what to say or do when he was around me. That’s why he went out last night.

‘Crime reporter’ would be the perfect job for a criminal. He could know what the cops were thinking and he could feed that information into the underworld. His fourth commandment of crime reporting was:

Sometimes criminals will try to make you see things their way. These are dangerous and often charismatic characters. You need to be clear with people which side of the law you sit on.

But what if Harry hadn’t been clear? He had been reporting crime for forty years. That’s a long time to interact with these ‘charismatic characters’ and stay clean. Maybe he started out on the right side but at some stage he slipped. But that sounded suspiciously like a crazy plotline for one of my comics. It was ridiculous. My father was a crime reporter, not a criminal.

A sound popped out from the general background hum of traffic: the rev of an engine close by. I crutched over to the window and looked into the yard. There was an old guy down there with long silver hair but a bald patch on top. The caretaker of the building. He was climbing out of a rusty white ute parked right next to the bin shed, near where the man had fallen. The caretaker was wearing grey overalls, the kind that cover your arms and legs. I’d watched him come and go a couple of times during the week. When you’re stuck in an apartment by yourself every day you get to know the rhythm of the place. His shoulders were rounded, neck bent forward. He reminded me of a tortoise, especially on the day, earlier in the week, when he had worn the backpack for weed-spraying.

He clicked the door of the ute shut then walked back out of the gate and hauled all the bins in, two at a time, parking them in the bin shed. When he was done he poked his head out of the shed, looked around the yard, then up at the building. I pulled back from the window. I left it a few seconds, then I looked down again.

The man went into the shed and was out of view for maybe half a minute. I watched and waited. He emerged carrying a couple of black plastic bags. I wondered if they had been in there when I went through the shed last night or if they had been put there since. I slid my phone out of my pocket and took three quick shots of him as he threw the bags into the tray of his ute. He looked around and up again, then walked towards the building. I had to press my face right against the glass to keep him in view. I tried taking another shot but it was all reflection and windowsill. I wanted to open the window but was worried the noise would alert him.

He opened a door or a gate at the base of the building. I had seen him put a lawnmower in there earlier in the week. On Tuesday, I thought. The gate made a clink-screek sound as it opened.

I had heard that sound several times during the week. The clink of a metal latch, then the screek of rusty hinges as the gate opened. It w

as the sound I had heard last night after I saw the man standing over the body, after he looked up at me and I pulled back from the window.

Clink-screek.

Had he hidden something in that cupboard? And what if the thing was still there?

I leaned out the window to get a better look but the caretaker just closed the gate with a screek-clink and threw a shovel and a piece of folded black plastic into the back of his ute.

I needed to go down there. This guy had to be involved in some way.

Stay inside. Don’t go anywhere. That’s what Harry had told me. I would not break the one rule my dad had set for me.

But what if I could be useful? What if breaking the rule meant that I could uncover fresh evidence? Wouldn’t that make him proud?

THIRTEEN

THE RETURN

I crutched through the bin shed – grim, even during the day. It smelt vegetabley and organic, worse than I remembered from the night before.

I had always loved puzzles and stories but I had never had anything to investigate before. Nothing had ever happened to me. Life was dull at home. Small town. Overprotective mum. School. Friends. Girls I loved but who didn’t love me so much. Now this.

I played last night over in my mind, from the moment I woke at 2.08 am through to the man following me upstairs.

Clink-screek.

That sound.

Clink-screek.

I’d heard it just after he looked at me, before I went downstairs. That sound would lead me to the body, I was sure of it.

I looked out the bin shed door. The caretaker’s ute was gone, leaving tyre tracks just metres from where the man had fallen to the ground.

Two trains rattled noisily by, one lumbering slowly, the other with places to go, people to see. Passengers were packed in, wearing suits and smart clothes. Regular people with regular lives, tapping their phone screens and reading their Friday-morning newspapers. People who had slept more than a couple of hours, and not in a cleaning cupboard. People who had not seen a man die in the night. This crime would not be in the news. Not yet.

I looked to where the man had lain and thought I could still make out the depression in the earth that I had felt with my fingertips the night before. Maybe I was imagining it. I scanned around for the other arm of the glasses and the lenses, but could see nothing. Maybe the larger man had picked them up, taken them with him.

I could see the little gate of the caretaker’s storage cupboard set into the wall. It looked like an entrance for elves or hobbits. It was only about the height of my bellybutton.

Clink. Latch. Screek. Hinges. There was no padlock on the cupboard. Anyone could hide anything in there. The man with that round face and those dead eyes could easily have dragged the body in there. And if he did the caretaker would have seen it just now, which would mean that he was definitely involved.

I would have to break cover to get across to the gate. I would be out in the open and could easily be seen from above. I wished that snooping was not in my DNA. I looked up through the tree branches. No humans. Just windows reflecting dark grey clouds above. Another storm on the way.

I eased my way along the outside wall of the bin shed, pressing myself against the rusty corrugated iron, then edged across the three or four metres of brick wall till I was standing right next to the storage cupboard.

The body will not be in there. Even if it had been, the man would have moved it by now, I told myself. I wanted to believe it.

I reached for the gate latch and felt a tingle in my jaw. I lifted the latch. It made a quiet tinkling sound. I pinched it between my fingers for a few seconds. I dropped it and there was a distinctive clink. I pulled it open slowly, closing my eyes for the first few centimetres. The hinge screeeeeeked, long and slow. I stepped back, bent down and peeked inside, squinting into the darkness. I could see the handles of five or six garden tools and, further in, the mower handle. I pulled the gate open some more.

Screeeeeeeek.

More tools and an earthy underground smell that stuck to my nostrils. Not disgusting like the bin shed but deep, moist and soily. Like a grave. The smell sat like a large piece of fruit in my throat.

The storage space went back a long way. It was too dark to see what was in there past the mower. There was a light switch on the wall to the right, below a shelf holding paint and weedkiller and hand tools. The switch was grubby with finger marks. I flicked it and a light globe snapped to life on the ceiling about two metres in. I peered in beyond the tools and paint and mower for anything that might hide a body – a sack or more of that black plastic.

There were piles of old tiles, some bricks, a stack of dark timber with long, rusted nails sticking out of it. I willed myself to go inside and look up the back. That’s what Harry Garner would do. He was known for going the extra distance to get the story. Commandment number ten:

Show determination, patience, mindfulness. Evaluate all evidence.

Harry was brave and determined. Was I?

FOURTEEN

TOOTH

I leaned my crutches against the wall outside and climbed in over the lawnmower. A spear of pain jabbed me just above the knee as I twisted and knocked it against the mower’s engine. My mum would be so mad with me. I was supposed to be on bed-rest for the week.

I leaned against the wall and tools clanked together behind me. My hunched body cast a misshapen shadow on the rear wall of the low, rectangular cavern. The air was cooler and earthier the further I moved in.

I took a ton of photos, hoping that I could look back later and find a little detail, a piece of evidence that might unlock something. I took pictures of the dusty ground beneath the beat-up Adidas on my left foot. I took shots of the blade of a shovel and a pair of long-nosed garden shears. The images were blurred and grainy so I flicked on the flash. There was an explosion of white as I photographed a crumpled piece of grey clothing on the ground. Is that the colour he had been wearing? The small man? I poked it gently with my shoe, spreading it out and revealing a pair of grey overalls spattered in white paint, grease and dirt. The caretaker’s overalls, the same kind he’d been wearing earlier.

I took another photo and, again, the flash blew the image bright white. It made me think of the reporters and police forensics experts in the stack of 1950s and 1960s crime reporter comic books I had under my bed. Harry had sent them to me on my seventh birthday and I had read each one dozens of times. The comics had names like Authentic Police Cases and Crime Smashers – The Law Always Wins. The reporters used old cameras with giant round flashbulbs that exploded and had to be replaced after each use. In the front of the comic was an ad for cameras with exploding flashbulbs and, in the back, a coupon to buy a Simplex Typewriter for $2.98.

The books were from when my dad was a boy. They were the only things he had ever sent me. I wondered what had prompted that – why, for one moment, he decided to reach out and then went quiet for another six years. Mum thought they were inappropriate, which made them even more fun to read. Reading them and drawing my own comics made me feel closer to my dad – taking down bad guys, smashing crime and using lines like, ‘We’ve finally found your hideout, you crook. Now we’ll send you away for a long stretch. See?’ They always said ‘See?’ at the end of a line in those old books, so that’s the way they spoke in my Harry Garner: Crime Reporter comics, too.

I flicked my phone to ‘torch’, turned the light towards the very back of the low, narrow space and saw five plump white bags of fertiliser. On the side of the bags were the words ‘OSCO Fertiliser Co’ in brown lettering and an illustration of a barn with chickens running around. The bags were about a metre tall and they weren’t leaning directly against the back wall. The tops of the bags were about thirty centimetres out from the wall and the bottoms of the bags were even further, which made me think there must be something behind them.

I felt cramped and claustrophobic. I looked back at the square opening. I imagined someone closing the gate from the outside – screek-clink �

� and me being locked in here with whatever was behind those bags of fertiliser. I wanted out.

But I’d come so far.

Determination, patience, mindfulness. Evaluate all evidence.

All evidence.

I looked back at the bags.

I tried to control the fear inside me, imagining the colour-gauge Margo, my coach, had shown me for controlling anger. I tried to imagine the fear dialling back from deep, volcanic red to orange and then back into the blues and greens. This helped me a little, but not much.

I would check behind the bags. There would be nothing there. I would rule out one more possibility. I would move quickly towards the exit and up the stairs, into the apartment. I would lock the deadlocks my father had installed and I would not leave the apartment again today. I would be safe.

I reached behind me for a garden tool and remembered the shovel the caretaker had thrown into his ute. I kept my eyes fixed on the bags. My fingers clasped the splintery wooden handle of a pitchfork. I swung the long, sharp trident around and poked it towards the bags. I had never wanted and not wanted something at the same time as much as I did in that moment. If this was the body, then I had helped solve a crime. But if this was the body, I was alone inside a small, dark cupboard with a dead human.

I figured that if it came alive – if I saw a skeletal hand shoot up from behind the bag and I heard a hideous crushed-metal laugh, then the gate swinging closed behind me – at least I had a pitchfork. In comics, it was always a popular tool when dealing with the undead.

I leaned against the wall, using my left hand to hold my phone for light and my right to hold the fork. I poked the three sharp prongs into the bag and pulled, raking it back towards me. I prepared for the worst but the bag was heavy. The fork came free then fell from the handle, dropping to the dirt floor. The bag remained in place.

I jammed the end of my phone into my mouth, trying to keep the light trained on the bags. I took the pitchfork in both hands and poked it deep into the top of the bag, hearing the plastic pop and feeling the prongs slide into the fertiliser. I dragged the bag back again. The phone dropped from my mouth and, for the next few seconds, I was pure panic. I couldn’t see what was behind the bag. The phone had landed torch down, the bag had landed on my foot and the back of the cupboard was dead dark. I dropped the fork, picked up the phone and shone it into the space where the bag had been.

On the Run

On the Run Two Wolves

Two Wolves Mac Slater Coolhunter 1

Mac Slater Coolhunter 1 The Fall

The Fall My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up

My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up My Life and Other Failed Experiments

My Life and Other Failed Experiments My Life and Other Exploding Chickens

My Life and Other Exploding Chickens My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong

My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Galactic Adventures

Galactic Adventures Mac Slater Coolhunter 2

Mac Slater Coolhunter 2 My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins