- Home

- Tristan Bancks

Galactic Adventures

Galactic Adventures Read online

Tristan Bancks tells stories for the page and screen. He has a background as an actor and film maker in Australia and the UK. His short films have won a number of awards and have screened widely in festivals and on TV. Tristan has written several books for kids and teens, including the explosive Mac Slater, Coolhunter series (Random House) released in Australia and the US, and his illustrated series, Nit Boy (Laguna Bay Publishing), about everybody’s favourite mini-beasts. Nit Boy is currently being developed for television. Tristan’s young adult novel, It’s yr life (Random House) was co-written via email between Byron Bay and L.A. with actress/author, Tempany Deckert. Tristan is saving for his ticket to space. He loves telling inspiring, fast-moving stories for young people.

www.tristanbancks.com

Also by Tristan Bancks

Mac Slater Coolhunter series

Nit Boy series

It’s yr life

For Hux and Luca.

Dream big.

‘A bit of advice given to a young Native American at the time of his initiation:

“As you go the way of life,

you will see a great chasm.

Jump.

It is not as wide as you think.”’

– Joseph Campbell

A Joseph Campbell Companion

Prologue

In 1971, two years after the first moon landing, the US government secretly attempted to send three children into space. The craft, containing thirteen-year-old Douglas Bailey, eleven-year-old Meredene Holden and nine-year-old Robert White, exploded before it left earth.

Now, over 40 years later, five more children are being given the chance to become the first kids in space. This is their story.

1. G-Force

‘Dash Campbell. You ready?’

I nod.

‘3, 2, 1 . . . Engage.’

I feel the pod move under me. My head and shoulders are thrust back into the red leather seat. The washed-out monitor in front of me shows a live video image of my face. Numbers jitter across the top of the screen. The number on top right flips quickly from 1G to 1.5, up to 2G. Then 2.5G to 3G. 3G means that the pressure I’m feeling on my body is three times my regular body weight. My arms are pinned to the armrests. I feel like I’m being fired from a cannon directly into the air, but I haven’t even left the ground.

I grit my teeth.

‘That’s right,’ says the voice in my headset, an Eastern European accent. ‘Mouth closed. One, two, breathe.’

They warned me in the briefing that my jaw could break if I opened my mouth.

I’m locked inside a TSF-18 centrifuge: 300,000 kilograms, top speed 270 kilometres an hour. It’s used to prepare astronauts for rocketing in and out of the earth’s atmosphere. The centrifuge is a round metal pod on the end of a 20-metre-long steel arm. I’m inside the pod, swinging round and round a white circular room in the Galactic Adventures Spaceport somewhere in the Mojave Desert, Nevada, USA. I’m a long, long way from home.

‘One, two, breathe.’

As the intensity of the G-Force creeps up I can feel my face starting to deform. My eye sockets are stretching. My vision’s blurring. Now it’s at 4Gs. I can see my cheeks smearing across my face in the monitor. I look scary, like an alien. My body’s clocking four times its regular weight because of the high-speed spinning of the centrifuge.

My right hand is gripping a joystick. My thumb is pressing a red button firmly. I know that if I vomit, freak out, or if I let go of the button before my five minutes are up, I can say goodbye to the only chance I might ever get to go into space – the only thing I’ve ever really wanted to do. But I don’t know if I can hold on much longer.

4.3G.

‘Squeeze your stomach. Breathe.’

I take a breath, using my diaphragm, not my chest. They warned me that if I let my chest collapse I might not be able to breathe in again.

A minute passes.

‘Okay, we are going to push through to 5Gs now. Are you ready?’

I don’t say anything. I can’t. Tears start to roll out of my eyes. The pressure of the centrifuge pushes them back into my hair. I grip the controller even tighter, trying to stop myself from letting go of the button.

‘Are you okay in there?’ the voice says.

Sweat makes my eyes sting. I blink hard. I want to wipe them, but I can’t lift my arm. My heart bangs fast.

‘Dash? Are we “go” for 5G?’

‘Yep.’ It’s all I can eke out.

I try lifting my head off the headrest even though they told me not to: ‘It may result in unrecoverable loss of head position.’ The extra acceleration kicks in and I feel like I’m being buried in sand. There’s a rushing in my gut. The lunch train has pulled out of Stomach Station and is roaring up through the tunnel towards Mouth.

That’s it. My thumb half-releases the red button. I’m not going to let myself hurl. I’m just about to release the button fully and stop the machine, when I feel a little twitch in the pocket of my grey hoodie and I press the button firmly again. The pocket twitch is Marv, my rat. I’m not, officially, supposed to have a pet rat at the spaceport, but Marv’s kind of my best friend. I snuck him onto the flight from Australia. We need each other.

The screen reads 4.7G and I begin to lose the edge of my vision, as though I’m staring into a tunnel. I hit 4.9 and, finally, 5G. The pressure I’m feeling is five times my body weight. My eyeballs are squeezing their way past my ears, into the back of my skull.

‘Okay, 3, 2 . . .’ says the voice in my headset.

I feel a really bad burning in my throat. Then the lunch train pulls into my mouth. My cheeks flex out.

‘1 . . . and . . .’ The pod begins to slow. The acceleration drops away rapidly. All the tension in my body slackens. Blood speeds to my head, causing a deep, warm rush, like when you stand up too quickly, but times a thousand.

Marv runs out of my hoodie pocket and up my chest to my neck. I’m on camera, so I grab him and shove him back in my pocket, hoping that no one has noticed.

The pod comes to a stop. I sit for a minute, just breathing, knowing I’ve survived one more challenge, the last challenge before the five are chosen. My heart rate begins to slow down.

The pod door hisses open. Heath, a spaceport worker, grey hair, bushy moustache, sticks his head inside.

‘How’d you do?’ he asks. ‘Looked like you were gettin’ upset in there. We were gonna pull the plug.’

I force a smile and swallow what’s in my mouth. It tastes real bad.

‘What’s next?’ I croak.

2. First Kids in Space

Two months ago, almost to the day, I was sitting, eyes glued to the computer screen in the back office of our laundromat. There were post-it notes in my stepdad, Karl’s, messy scrawl stuck around the edge of the screen.

‘Join the ranks of the greatest explorers in human history,’ said James Johnston, the old man on-screen. He was wearing a white cowboy hat and he had wild, silver hair spewing from his nose, ears and eyebrows. ‘Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, Neil Armstrong . . . and you.’

I’d been waiting for this moment nearly my whole life. But I refused to believe it till I actually heard him say the words. I cranked the volume and closed the door to drown out the noise of ten washing machines, five dryers and the highway out the front.

‘When I was twelve years old,’ he said in his Irish accent, ‘I sent a letter to NASA offering to be the first kid in space. They didn’t write back. I’m now slightly too old to be the first kid. But not too old to give you the chance to make that pioneering

leap for humankind.’

I figured pretty much every kid in the world with web access was watching Johnston’s announcement at that moment.

‘I invite children everywhere,’ he said, giving a raspy cough and taking a sip from a tall glass of water, ‘to upload a one-minute video to firstkidsinspace.com. You must show me why you, out of all the children on earth, should be one of the first five kids in space. You have one week to submit your video. Twenty children will be chosen to spend a week at my spaceport facility in Nevada. They will be put through a week-long training and medical assessment program. The top five participants will then spend one month at Space School. Space travel puts extraordinary stress on the human body and you must be exceptionally fit. You will be blasting beyond earth’s atmosphere at three times the speed of sound. If you survive Space School, you will experience ten incredible days of weightlessness aboard my Utopia Space Station, orbiting earth more than 150 times.’

I tried to stay calm as I jotted down the details:

1 min. video

20 kids chosen

Top 5 = 1 month Space School

Survive that → Utopia

Johnston leant in to camera, lowering his voice. I leant in a little, too. I wanted to catch every word.

‘Children will be needed on future long-range missions to distant planets and also for long-term stays on space stations like Utopia. Children will be vital for their advanced computer skills, technical expertise and adaptability. I believe in children. Our top five will, officially, be the first kids in space. Will you be one of them?’

The screen cut to black, then Galactic’s silver star logo faded up with the web address. I sat there, buzzing all over. Then Karl, my stepdad, shoved open the door, letting real life spill inside. ‘What are you doing? We’ve got a heap of clothes wash. Get onto it,’ he said.

‘But I’ve just—’

‘Move it!’

I pocketed the envelope that I’d written my notes on and headed out to the baskets of dirty washing. I picked up the biggest pair of underpants I’d ever seen. On any other day I would have been totally freaked by what was inside them. But, that afternoon, I was so fired up it was as though skid marks didn’t even exist.

I worked for two hours, went out on deliveries, then I made dinner – just three out of the million jobs on my list. I opened the fridge to find one floppy brown carrot, a bottle of beer, an empty tub of margarine, some rock-hard cheese with cracks in it, three eggs, a plastic bag with two bread crusts and an old green vegetable of some kind. I grabbed the eggs and crusts. The eggs kind of smelt a bit when I cracked them, but I scrambled them anyway and dumped them on toast with some no-name beans. I choked mine down in front of the TV without even thinking about how bad it was. My head was already in space.

Karl sat next to me on the couch to watch a current affairs show. Top stories were, ‘Are Big Macs as Big as They Used to Be?’ and ‘Is Your Bra Killing You?’ My brother Chris’s armchair lay empty to my left. It had been that way for a year since he got his apprenticeship and moved out. He wanted to be a mechanic. He hardly ever dropped over now, even though he only lived four streets away.

I knew exactly what would happen next. Karl would say, ‘That was good, Rocket. You’re a chef.’ That’s what he always called me, Rocket. Then he’d take the dishes, dump them in the sink, come back and pass out on the couch for a couple of hours. I’d nudge him just before nine. He’d go down, close up the laundromat (it’s right underneath our apartment), then we’d shake hands and go to bed. Seven days a week, the same thing. But, tonight, I felt like I had something to live for.

The second I got home from school the next day I dumped my bag and slipped downstairs to the car park under the laundromat. It was dark and the air was cool. I pulled my jacket around me and zipped. Each car space was sectioned off by wire fencing and a gate. Everyone stored old furniture and junk in their space. We couldn’t even fit the car in anymore; we had to park on the street.

I pushed the wire gate open, knelt down, lifted the lid on my old timber chest. The hinges squeaked and I gazed in at the contents – empty orange juice bottles, random bits of metal, plastic pipe, corks, straws, balsa wood, parachutes and tools. All the things I needed to make my spacecraft. I picked up a bottle, then some scrap aluminium that I could use for a nose cone. I set them aside. I grabbed the long-nose pliers, sat down and started building. I loved that feeling more than anything. It was the one place I felt really good – alone on the cool concrete in the dimly lit car park, dreaming of space and building a rocket. I was going to make the best one-minute video ever and earn my place in space.

‘Stand back!’ I shouted, running for cover. ‘BOOOM!’ an almost deafening roar, as plastic shards sprayed everywhere and an orange juice-bottle rocket soared out of the alley behind the car park and up into the dusky sky. I traced its path with our old video camera as it zizzed off towards the pink clouds. Then I turned the camera on myself and gave it everything I could, explaining to the judges why I needed to be one of the First Kids.

My video was one of nineteen million from 67 countries that poured in to the site over the next two weeks. Galactic Adventures had 5,000 people trawling through the entries at their HQ in Nevada. Their decisions would make history. No one would forget the names of the first five kids in space.

But not everybody was excited about the idea of loading children onto a rocket plane and firing them into infinity. I scanned the news every day and all these parents and teachers, politicians, lawyers, bloggers, talk-radio dudes and even the head of NASA were speaking out, saying that this was totally irresponsible.

‘Space is not for kids!’ they said. Health experts spoke of the dangers of radiation on growing bodies. Someone registered the domain name ‘spaceisnotforkids.com’ and it became a hub for the growing protest movement.

On the bus to school I heard a professor on the radio say, ‘We are putting innocent children’s lives on the line to feed James Johnston’s self-interest. The man is an egomaniac.’

The ‘Space is Not For Kids’ campaigners wanted prime ministers and presidents to ban the competition. There were protests outside the spaceport. People marched and signed petitions. They blogged and emailed letters to the editors of news sites, trying to stop kids from going into space.

In the end, though, it was ruled to be a legal competition and if the winning kids’ parents were happy to send them into space, there was nothing anyone could do about it. Not school principals, judges, presidents or NASA. Kids were going to space and that was that.

3. Gone

I still remember the feeling when the call came in.

I was in my room, lying on my bed, bored off my brain. I was peeling flaky lead-based paint off the wall and letting the pieces crumble from my fingers onto the floor. I looked up at the first model rocket plane I’d ever built. Me and Karl had made it out of matchsticks when I was six. It took forever, but we worked on it every night till it was done. The plane had hung on fishing line from my bedroom ceiling ever since. It twisted gently in the warm breeze from the open window. I could see the pilot that I’d painted in the cockpit. That pilot was me.

We built the plane after I came back from a week at my grandfather’s place. I was six, and that week was the beginning of my obsession with space travel. I only met my grandfather once, but I’ll remember those few days forever. Me and Chris, my bro, were sent down there on the plane by ourselves.

My grandfather lived near a place called Woomera in South Australia, a few hours north of Adelaide. Back in the day Woomera was used for American and British rocket launches and deep space research. It was even used during the moon landing. My gramps was one of the caretakers. When I went there, the range was old and crumbly and it hadn’t been used much in years, but he said, ‘The Americans are back and they’re testing out a new spaceplane.’

My grandfa

ther’s house was at the far end of the test range. Every morning, when we were eating breakfast, we’d hear this incredible noise as a plane charged up the runway. For the first couple of days, when I’d hear it, I’d drop my spoon, race to the window and just catch them taking off. They’d fly low over his house, before soaring steeply into the sky. The vibrations were so intense that things dropped off the shelves. I remember my gramps getting hit on the head by a blue teacup.

One day, towards the end of the week, I asked him if I could go outside and watch. So we went and lay in the paddock out front and waited, blocking our ears as a plane tore up the runway and screamed right over us. There was an explosion of wind-rush and the grass waved wildly all around, whipping my freezing cold ears.

The next day at the same time I ran out there and felt the same buzz all over again. The planes flew so low and turned so steeply that I could actually see the pilots inside. I could see their faces and my mind blurred the line between them and me. I felt like I was up there flying the plane. Then they’d turn hard and climb quickly into the sky.

‘They’re going into space!’ my grandfather would howl. That’s how I knew it was possible. People, real humans, could actually do it. That was the only exciting thing that happened when I was little.

At the end of the week, when we went back to Sydney, my mum wasn’t there. Only Karl. I kept asking where she was and I remember him sitting me and Chris down on these orange-and-green plastic chairs near the steamy front window of the laundromat. It was where customers would read old copies of Woman’s Day and New Idea while they waited for their clothes to dry. It was really noisy with all the machines going full tilt and the traffic outside. Karl crouched down in front of us and said, ‘Your mum. She’s gone.’ I didn’t really know what that meant.

‘Did she die?’ I asked and my bro hit me in the arm.

On the Run

On the Run Two Wolves

Two Wolves Mac Slater Coolhunter 1

Mac Slater Coolhunter 1 The Fall

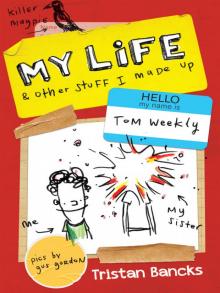

The Fall My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up

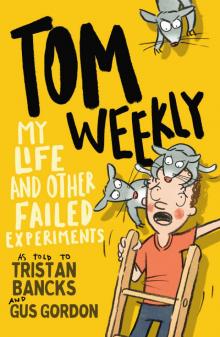

My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up My Life and Other Failed Experiments

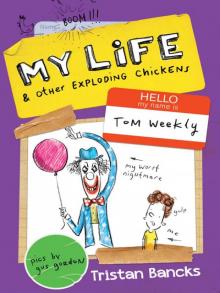

My Life and Other Failed Experiments My Life and Other Exploding Chickens

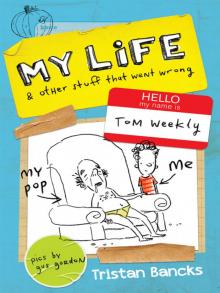

My Life and Other Exploding Chickens My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong

My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Galactic Adventures

Galactic Adventures Mac Slater Coolhunter 2

Mac Slater Coolhunter 2 My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins