- Home

- Tristan Bancks

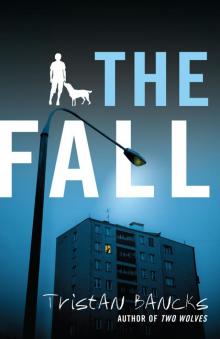

The Fall

The Fall Read online

About the Book

In the middle of the night, Sam is woken by angry voices from the apartment above.

He goes to the window to see what’s happening – only to hear a struggle, and see a body fall from the sixth-floor balcony. Pushed, Sam thinks.

Sam goes to wake his father, Harry, a crime reporter, but Harry is gone. And when Sam goes downstairs, the body is gone, too. But someone has seen Sam, and knows what he’s witnessed.

The next twenty-four hours could be his last.

CONTENTS

COVER

ABOUT THE BOOK

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

ONE: THE FALL

TWO: ALONE

THREE: DOWN

FOUR: THE BODY

FIVE: THE CUPBOARD UNDER THE STAIRS

SIX: THE APARTMENT

SEVEN: THE VISITOR

EIGHT: HOW I WONDER WHO YOU ARE

NINE: TRUST ME

TEN: SOLVE IT

ELEVEN: HARRY GARNER’S TOP TEN COMMANDMENTS OF CRIME REPORTING

TWELVE: SNOOP

THIRTEEN: THE RETURN

FOURTEEN: TOOTH

FIFTEEN: THE GIRL FROM UPSTAIRS

SIXTEEN: A SAFE PLACE TO HIDE

SEVENTEEN: DEAR DAD …

EIGHTEEN: STAKEOUT

NINETEEN: INTERROGATION ROOM

TWENTY: ALONE BUT NOT LONELY

TWENTY-ONE: MISSING JOURNALIST

TWENTY-TWO: COP

TWENTY-THREE: RUN

TWENTY-FOUR: HOW IT FEELS

TWENTY-FIVE: 6A OR 6B

TWENTY-SIX: SCARLET’S APARTMENT

TWENTY-SEVEN: CODECRACKER

TWENTY-EIGHT: SURVEILLANCE

TWENTY-NINE: IN THE BUILDING

THIRTY: SIEGE

THIRTY-ONE: BOOT

THIRTY-TWO: ALL IS LOST

THIRTY-THREE: SILENT PRAYER

THIRTY-FOUR: NOW OR NEVER

THIRTY-FIVE: THE FALL

THIRTY-SIX: FUNERAL

THIRTY-SEVEN: HOME

THIRTY-EIGHT: SAM GARNER’S TEN COMMANDMENTS OF LIFE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT TRISTAN BANCKS AND ROOM TO READ

ALSO BY TRISTAN BANCKS

READ ON FOR A SAMPLE OF TRISTAN BANCKS’ AWARD-WINNING NOVEL TWO WOLVES

COPYRIGHT NOTICE

For Hux

ONE

THE FALL

I woke to the sound of a voice pleading, high-pitched and urgent. I listened with my whole body. The man’s voice was coming from the apartment above. Or was it below? I couldn’t be sure. In the six days I’d been staying with my father I hadn’t heard much noise from the other apartments.

The microwave in the kitchenette read 2.08 am. My father had left the heaters on too warm again so my head was fuzzy and my throat was dead dry.

I sat up and the springs on the sofa bed squeaked. There were footsteps across the floor above now, and another man’s voice, low and threatening. I rolled off the couch, grabbed my crutches and stumbled to the wide window. I wiped the foggy glass with the palm of my hand, my bruised armpits resting painfully on the hard rubber crutch-tops. I looked out through the branches of a tall, leafless tree and across a yard to a wire fence and a mess of railway tracks beyond.

It was raining lightly. People said that winter had come early to the city this year but in the Mountains, where I lived with Mum, it was much colder than this already. I twisted the old latch and squawked the window open a little, pulling it in towards me. I put my ear to the narrow opening and was struck in the face by a rectangle of cold.

I listened.

The men’s voices sounded louder now but I still couldn’t make out what they were saying. I opened the window a little more, stuck my head out and looked up and to my left. I could see someone’s fingers curled over a balcony railing. All of the apartments had balconies but they didn’t hang out over the edge. They were set into the building next to the rear windows. That’s where the voices were coming from. The man who was pleading sounded small and thin, like a jockey. Another man was rough and phlegmy like he had crunchy gravel caught in his throat. He sounded stubborn, bullish, like Mr Mawson, my science teacher.

Something bumped my leg. I pulled my head back inside and looked down to see Magic, my father’s dog. My parents split up before I was born so Mum got me and my dad got Magic. Some days Mum acted like she got a raw deal. That’s why she called my father ‘The Magic Thief’. And for other reasons, I suspected.

Magic shook her head from side to side, her long ears slapping loudly against the top and sides of her head.

‘Shhhhh, girl,’ I whispered, rubbing one of those silky, soft ears for comfort. Magic was the oldest, fattest, brownest dog in the world. Also, the funniest. I had spent more time with her this week than I had with my dad.

On the balcony upstairs, the men’s argument intensified. I listened hard but the wind and rain seemed to dampen their voices. I thought about waking my father but I wasn’t sure Harry would appreciate it. That’s what he liked to be called – ‘Harry’. Never ‘Dad’.

The bigger-sounding guy coughed hard then spat over the balcony. The little guy raised his voice. One of them must have slammed against the railing or a door or wall. I could feel the impact through the window frame. I squeezed Magic’s ear hard with my free hand and she yelped quietly.

‘Sorry,’ I whispered.

I wanted to drink in every detail, like my father would when he was out covering a story. I turned to the microwave. It was 2.11 am. The small man screamed but the voice was quickly stifled, maybe by a hand. I turned back just in time to see a flash of black as something fell past my window.

Someone.

He flapped his arms and clawed at the air, trying desperately to hold onto something. He let out a strangled yawp as he fell.

Pushed was my immediate thought. He didn’t just fall. He was pushed.

I heard the impact and stared down through the gnarled tree branches at the body lying facedown in the mud beside the bin shed.

The body.

I was almost thirteen years old and I had never seen a dead human being before. At least, I figured the man must be dead. It’s further than you think, six storeys. He lay there, his body buckled, a crumpled mess of limbs, lit by a single railway security light on a pole at the edge of the train tracks. I wished that I hadn’t seen it. Now I couldn’t ‘unsee’ it. I felt like this image would be scorched into my brain forever. I wished I hadn’t begged to come to my father’s in the first place, and that I hadn’t behaved so badly that my mother had finally agreed.

A siren cut through the constant hum of traffic noise. Next came footsteps on the floor above, then the distant squeal of an apartment door. I turned and crutched across the seagrass matting to the bedroom, swinging my legs forward then reaching ahead with the crutches, not even feeling the pain in my armpits now.

‘Harry,’ I whispered.

No response.

‘Harry!’

I went to his bedside and shook the rumpled quilt but it gave way. I pulled the quilt back. My panic deepened. I fumbled for the lamp switch and flicked it on.

There was no one in the room but me.

TWO

ALONE

I heard the rattle of the old lift climbing upwards, past our apartment, then the low thunk of it arriving on the sixth floor. I listened intently as the doors opened, closed and the lift clattered down again. I could imagine the scene in one of my comics: the large, dark shape of the man seen through the crisscross wire mesh window of the lift door.

I twisted awkwardly and crutched out of the bedroom to the bathroom door, which was open just a crack.

‘Harry?’

I shoved the door with the

bottom of my crutch. Every nerve in my body lit up. The room was empty and dead dark, no windows. I flicked the dull light on, revealing old blue tiles, mouldy shower curtain, cracked mirror and the rust stain on the bath from the tap that would not stop dripping. But no Harry. I switched off the light.

It was a small, shabby one-bedroom apartment – a lounge room, sparsely furnished, with a crusty old kitchenette and noisy fridge on one wall, then the bedroom, bathroom and a small balcony. I slept in the lounge room. The front door led to the lift and stairs. There was nowhere else that my father could have been.

I headed back across the lounge room towards the window, whacking my right knee on the edge of the sofa bed and sending 50,000 volts of pain surging through my body. I swallowed a scream and squeezed the bandage on my knee, just above where they’d cut me open and inserted six large metal staples ten days ago. I dug my fingers in hard and stayed there, hunched over my pain in the darkness, thinking about my dad and trying not to cry.

Once the electric agony had softened to a dull throb, I stood and struggled back to the window, edging an eye out over the ledge. I looked down through the crooked, leafless branches and saw the shape there – a man twisted up like a pretzel, rain falling on his body. He did not move. I wanted to call out to the other people in the building. I wanted to scream loud enough to wake the people in the skyscrapers studded with lights on the far side of the railway tracks and beyond the old railway sheds, but something told me not to.

The man who fell was not my father. I repeated it again and again, making it true.

Text Mum, I thought.

I had no call credit till the start of the new month but I still had unlimited texts. I ran out of call credit and data my first day at Harry’s. There was no landline in the apartment. Only Harry’s mobile. It was locked with a code, which I had unsuccessfully tried to crack. No wi-fi either. There were forty-seven different wi-fi signals available from other apartments and shops but every single one of them was locked.

Harry had only lived here for about a month. He said he didn’t plan on being here long, that it wasn’t worth getting the web connected and that I could do better things with my time than stare at a screen. He said he was a Luddite, which meant he was allergic to technology. He used it only when necessary. But I don’t think he understood the seriousness of the situation. Kids can die from wi-fi starvation.

Mum said Harry only ever lived anywhere for a few weeks or months before he moved on. She called him ‘itinerant’. I was pretty sure it wasn’t a compliment. Texting her now would only confirm her belief that my dad was a hopeless, irresponsible little man.

I’ll just pop out and grab some milk. I’ll only be a minute. You go off to sleep. It’s late.

That’s what he’d said. Milk. And now he was gone. But he couldn’t be gone. Fathers don’t just disappear. Especially fathers who you barely knew, had barely had a chance to know.

I tried not to see newspaper headlines with his name in them. I went to the sofa bed and pulled my backpack out from underneath. I took my phone from the front zip pocket and texted my dad. I knew it wasn’t worth it but I tried anyway.

WHERE R U?

I heard a bing from Harry’s bedroom. He only sometimes took his phone with him. He said it was too easy to track, that phone tower records could be used in court and crime reporters like him were being sprung for meeting with criminals and forced to dob in their best contacts.

I wanted to turn on a lamp for comfort but I stopped myself. I didn’t want anyone to know that someone was awake in this apartment. There was enough city light pouring in through the window for me to get around. Night-time in the Mountains was pitch-black with millions of stars but the city sky on a cloudy night seemed almost as bright as day.

I moved slowly, quietly to the window again and pushed it open a little more. When I saw what was down there, my breath froze in my throat. There was a large black umbrella. Someone was standing over the body. I flicked my phone to camera. Gather details. That’s what Harry Garner would do when he was out on a story. I wondered if he was a crime reporter because he loved details, or if he loved details because he was a crime reporter.

As I reached out the window, in my excitement I knocked the phone hard against the timber window frame, making a loud clunk. The umbrella shifted to the side and the shape beneath it looked up, directly at me. He was larger than I had thought. Even from up here he looked big. An elephant of a man. His face was white and round as the moon. His hair was silver and his eyes were lit up by the security lamp. I stepped back from the window onto my bad leg, pressing my hand hard against my mouth.

What have I done? Why did I look? I had seen everything and the man knew it.

I’d never met a murderer but I figured they probably didn’t like it much when they realised that someone had seen them committing their crime and then tried to take photos of them standing over the body.

He would come up here. I had to go.

The stairs. Harry had told me to always use the stairs. And the man had used the lift. I could go to the police station. I had seen one on the street when I arrived. Or I could go to the convenience store across the road. It would be open.

I pulled a pair of shorts on over my boxers. As I threw my phone into my backpack, I saw Harry’s laptop sitting on the dining table. He worked on it constantly when he was home. He would want me to take it with me. I put it in my bag too. As I shouldered the backpack an electricity bill fluttered from the table to the floor. I left it, crutching quickly towards the front door.

Clink-screek. A sound from the ground below. The man escaping? Or coming upstairs?

‘Magic, come,’ I whispered.

She lumbered across the seagrass matting, thrilled to be going for a walk.

THREE

DOWN

I eased my way, barefoot, down the creaky timber staircase. The cold wood bit the sole of my left foot each time it made contact with the stairs. I hadn’t crutched downstairs much. Tina, my favourite nurse at the hospital, had taught me on the fire exit just outside the ward. I tried to remember what she had said. Crutches first, then left foot, always keeping my right foot raised and out of harm’s way. If you swung your feet out first you could pole-vault down five or six stairs. Believe me. I knew.

I held tight to the crutch and Magic’s lead with my left hand to stop the 42-kilogram dog from losing her footing and shooting down the stairs like a furry torpedo and taking me with her. The collar pressing on Magic’s throat turned her noisy breathing into something like a bowsaw cutting down a thick gum tree.

The staircase smelt like mould and was lit by a cold, fluorescent strip light on each landing. There were two flights of stairs between each floor. Magic and I slowly weaved our way down.

‘Shhhhhh,’ I whispered to the noisy breather. I doubted that Magic had ever been walked in the thirteen years since my parents broke up. She didn’t even go outside to wee and poo, which, in my opinion, must be humiliating for a dog. She had a small doggy litter box in the bathroom and she didn’t like me watching her while she used it. In the time that I had been staying at Harry’s apartment, I had seen him feed Magic chocolate-chip biscuits, a whole banana, spaghetti bolognaise and half an extra-spicy Thai chicken pizza. So Magic’s weight and breathing problems weren’t a total mystery.

As we passed the two apartment doors on the third-floor landing I paused to listen, to make sure the man who had been standing over the body wasn’t using the staircase. I stared at 3A and 3B, wondering if either of them was unlocked. I thought about knocking and asking for help but my father had told me I wasn’t allowed to speak to anyone in the building. Harry was gone now, though, so why should I care about his stupid rules? The thought that he had left me alone in the apartment in the middle of the night made me angry. He had been upset with me before he left just after 10 pm – he hadn’t yelled or anything but I knew. I waited up for a bit but must have fallen asleep.

I’ll only be a minute. You go of

f to sleep. It’s late.

I could feel the wire coil of rage in my chest start to heat. That coil made me do stupid things. That coil was why I was here at Harry’s, why my mother had finally given up and sent me here after years of me badgering her. I tried to breathe, to stop it from glowing red.

Harry didn’t mean to stay out. He’s a good person. There must be a good reason.

‘You can’t be seen going in or out of the apartment. In fact I’d rather you didn’t go out on your own at all.’ That’s what he had said on the first morning.

‘Why?’ I’d asked.

‘A story I’m working on, something I’m involved with. I can’t go into it right now, but it’s important that you listen to me, okay?’

I had nodded.

‘Only the stairs, Sam. You promise me?’

At first I thought it was a bit harsh, him not letting me use the lift when I was on crutches. But then I realised that he was trusting me with his secret. I had no idea what that secret was but it still felt good to know that I had a role to play. I didn’t like the idea of crutching down all those stairs so I had spent the past six days inside: watching TV, playing my Xbox, writing a new comic book, trying to avoid the schoolwork Mum had made me bring and, at night, monitoring my father, trying to find out about the story he was working on.

On the Run

On the Run Two Wolves

Two Wolves Mac Slater Coolhunter 1

Mac Slater Coolhunter 1 The Fall

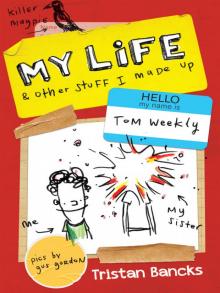

The Fall My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up

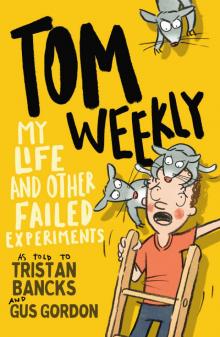

My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up My Life and Other Failed Experiments

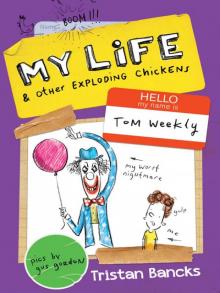

My Life and Other Failed Experiments My Life and Other Exploding Chickens

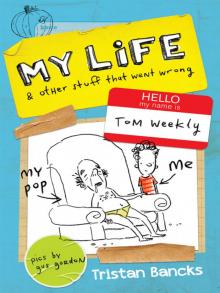

My Life and Other Exploding Chickens My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong

My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Galactic Adventures

Galactic Adventures Mac Slater Coolhunter 2

Mac Slater Coolhunter 2 My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins