- Home

- Tristan Bancks

Two Wolves Page 4

Two Wolves Read online

Page 4

Ben saw seventeen spiders. Every time he screamed or jumped back Dad would help him get over it by saying something like, ‘You want me to put a nappy on you? Just hit it with your shoe.’

Olive didn’t do anything. She just poked her tongue out and asked the same knock-knock joke over and over again. ‘Knock knock. Who’s there? Banana. Banana who? Banana walking down the street with his head split open.’ She’d made it up herself. Ben didn’t think she understood the principles of knock-knock jokes and he threatened to split her head open if she told him the joke again. Which she did. But he did not.

Ben kept himself occupied by stealing looks at the black plastic in the open roof space. He tried to imagine what it might be. What would his father hide in the roof and get so angry about? Chocolate? Beer?

As he worked, Ben found interesting things – peacock feathers, handmade arrows, two metal traps with tough steel jaws and an old, open safe with a combination lock. Dad sat and looked at it for a long time. When Ben asked why, Dad snorted and muttered something about Pop, then chucked the safe down the side of the cabin.

Ben found a copy of a book called My Side of the Mountain. He wasn’t a big reader but the book had an interesting cover – a kid in the wilderness with an eagle or a falcon flying down to sit on his arm. Ben suspected that things could get boring out here so he slipped the thin book into the back pocket of his school pants.

He asked Dad about things that he found, trying to make conversation as they worked, but Dad was even more distracted than usual. Ben desperately wanted to ask him what was going on with the cops and coming to the cabin and the thing in the roof and why Dad was so angry and when they could go home, but he thought better of it.

In the large, dark cupboard at the back, Ben found a hunting gun, old and rusty, and a bow for the arrows. He asked Dad about the gun and bow, and Dad grunted something about Pop hunting rabbits and then left the room.

Fishing rods, a rickety old ladder, loose pieces of timber. And that clump of black plastic. Ben wanted to ignore it but would-be detectives are curious by nature.

Mum was speaking to Dad out near the car. Ben tiptoed across the cabin and listened carefully from just inside the door.

‘Tell me when we’re leaving,’ Mum said in a low voice. ‘We’re in the middle of nowhere.’

‘I think that’s the idea.’

‘There’s no running water, no toilet. There’s not even phone reception. I hate it.’

‘Read your magazine,’ Dad snipped.

‘This wasn’t the deal.’

‘Let’s just pretend we’re adults for a minute, April. Think about it,’ Dad said. ‘Oi, Big Ears!’

Ben knew who Dad was talking to. He poked his head into the doorway. Dad gave Mum a look and walked toward Ben, who swallowed hard. Dad placed a hand on the back of his neck and spun him around so that they were both looking into the cabin.

‘What do you think?’ Dad said. The room was cleaned, restored and only smelt vaguely of mould now.

‘Not bad,’ Ben said.

‘Apart from listening in on conversations, you’ve played hard, done good.’ Dad took his hand off Ben’s neck. ‘Pull my finger.’

Ben did.

Parp. A sharp, loud trumpet sound from Dad’s behind.

‘Ray!’ Mum said.

Ben laughed but Dad didn’t crack a smile. He never did, which made it even funnier.

‘I’ve got to find some reception up the hill, make some calls.’ Dad headed for the car, grabbing his new phone off the front seat. He had bought himself and Mum new phones on the way up the coast and dumped their old ones in a bin outside the store. He walked off up the dirt road.

Ben watched until he disappeared around the corner. Mum went back to the far side of the clearing to lie on a rock in the sun. Olive sang loudly to herself and marched up and down a tree branch, barking orders to invisible people on the ground – something about her kingdom and loyal subjects. Ben wandered into the cabin. He looked up into the open roof space, his eyes settling on the crumpled black plastic sitting on a timber slat toward the back of the cabin.

Ben pushed the door closed and crossed the floor. He climbed onto the dark timber workbench to get a better view. He would be quiet and get this over with quickly.

He stood on his tiptoes and strained to see but he was too far away. Dad had used a chair to reach into the roof area but Ben was not tall enough for that.

Hungry.

So hungry. He had eaten a tiny morsel of chocolate as they cleaned up the cabin but that was it.

He slipped down from the hardwood bench and tried to push it but it wouldn’t budge. He moved in behind the bench and put all his weight against it, shoving with everything he had. It moved a few centimetres, grinding across the wooden floor. He gave it another push then crept to the door and looked out. No Dad. Mum still lying, lizard-like, on her rock on the opposite side of the clearing.

Ben rushed back across the cabin floor and pushed the bench about ten centimetres. He stopped, listened, breathed hard, shoved it another ten. Another low wood-on-wood groan. He wondered if he’d be able to reach the plastic now, but decided he needed to get another metre closer. He ran to the door and checked again, heart thumping lickety-split. Mum rolled over on her rock to face the cabin.

‘What are you doing?’ she called across the clearing.

‘Nothing,’ he yelled back. ‘Just bored.’

‘Well, find something to do,’ she said, closing her eyes. Olive was at the base of the tree now, still addressing her loyal subjects.

He ducked back inside. He would have to push the bench across the floor in one almighty shove. It would be loud but otherwise it would take forever and Dad would return. He gripped the thick timber edges of the old bench, stretched one leg back behind him and readied himself.

‘One, two, three . . .’ he whispered. The bench screamed across the floor and came to a stop. So loud. He stood, breathless.

‘Hi,’ said a voice. Ben’s heart leapt from his throat. He turned to the door.

‘Shhh!’ he hissed at Olive. ‘Get out!’

She stood there, bottom lip out, then she pointed at him and screamed, ‘YOU’RE MEAN!’ and ran away.

Ben eased the door closed. He heard Mum ask what had happened. He jumped up on the bench, reaching as high as he could. His fingers managed to push the black plastic aside enough to scrape the bottom of something, but not quite enough to get a hold on it. He reached again and opened the plastic further.

Ben recognised the bag as soon as he saw it. It was grey nylon with black handles. He positioned his toes on the very edge of the bench and reached for the stars, pinching a corner of the grey nylon. He steadied himself and pulled at the tiny corner of material. He seized a handful of bag and lost balance, falling off the edge of the bench and pulling the bag down on top of him. Large clumps of something fell out.

Ben landed awkwardly on his side. One of the clumps that had fallen from the bag lay on the floor in front of his face, lashed together with an elastic band. Ben took it in his hand and sat up. A serious-looking man with a large forehead, thick eyebrows and a bushy moustache stared back at him from the top of the pile he was holding. All around the man were pictures of cannons, soldiers, images of battle.

Ben was holding money. A lot of money. He had never in his life seen a single one hundred dollar note. Now he clutched a wad of the green bills. He smelt it to see if it was real but he had no idea what money was supposed to smell like. He flicked through it with his thumb. The pile of cash was four or five centimetres thick. How many hundred dollar notes would fit into a four-centimetre tall pile? Three hundred? Five hundred? Ben calculated it in his mind.

Could he really be holding $50,000? He glanced around and stood up to look in the bag, which lay twisted and open on the workbench. There were fifteen or twenty identical piles

of cash in the bag and on the floor.

Dad and Mum never had spare money, even for shoes or haircuts. One of Dad’s favourite sayings was ‘Money makes the world go round’ but most of the time their world stood still. Ben had missed out on the science excursion on sand dune ecology a week earlier because they didn’t have the fifteen dollars. But now they had lots of money. Why wasn’t it in the bank?

A noise out front. Ben grabbed the sports bag and stuffed thick blocks of cash back in, carefully watching the door and window. Fear roared through him, making him clumsy. He tried to close the bag but the zip was broken.

Dad said something to Mum. Ben’s throat closed. He jumped up on the bench and reached high, trying to shove the bag back into place, but he wasn’t tall enough. He took steady aim and threw the bag onto the wide timber slat but it fell back into his hands.

‘Where’s the boy?’ Dad called to Mum, his voice very near to the cabin now. Mum said something about Ben moving furniture.

He tried again, throwing the bag up onto the timber slat that ran across the roof beams. The bag held, but one end hung down, revealing the money. Dad’s footsteps sounded on the gravel near the cabin door. Ben jumped down, giving the workbench two tremendous shoves into position next to the wall just as Dad walked in. Ben breathed hard, guilt painted across his face in sweat.

‘What’re you up to?’ Dad said, propping just inside the door. ‘Decorating?’

Ben took a slow breath and said, ‘Yeah. I tried moving things around but I reckon it all looks best where you had it.’

Dad studied him for a few seconds. Ben took long, slow breaths.

‘Can we go outside?’ Ben asked.

‘What for?’

‘Explore . . . see the creek.’

Dad looked at him. ‘You sick? You never want to go outside.’

‘Yeah, but . . . there’s all this nature.’

Dad eyed him, walked to the table, grabbed his keys. ‘I’ve got to go out.’

‘Where to?’ Ben asked, an awkwardly long time after his father had spoken.

Dad shook his head and looked at Ben, puzzled. ‘You’re a weird bloke.’ He headed for the door.

Ben breathed out slowly and hope flooded in. He wished his father out of the cabin with everything in his soul.

Dad stopped in the doorway and turned, clicking his tongue like he had forgotten something. He looked up into the open roof space.

Dad walked slowly to the back of the cabin, looking up, squinting to be sure that he could see what he thought he saw. A bag hung from the roof beam, a wad of cash lolling out like a tongue.

Ben crabbed sideways toward the door.

‘Hey!’ Dad called. It didn’t sound like ‘Hey, you found my bag! I’d been meaning to tell you about the hundreds of thousands of dollars I’d hidden in the roof.’ It was more of a ‘Hey, you have about a second and a half before I explode like Vesuvius.’

Ben stopped.

Dad turned and lunged at Ben, grabbing him by the scruff of the neck. He marched Ben to the back of the cabin and tilted his head up.

‘What is this?’ he barked.

Ben looked at the bag: hanging, threatening to fall.

‘Is everything okay?’ Mum called from across the clearing.

‘Was this you?’ Dad shouted at Ben, daring him to lie.

Ben was too scared to say anything. The neck of his shirt was pulled tight against his throat. Difficult to breathe. He heard running.

Olive arrived in the doorway.

‘What happened?’ Olive asked.

‘You go climb the tree, sweetie,’ Mum said, arriving next to her.

‘But I –’

‘Go!’

Little footsteps.

Ben wanted to climb a tree too, for the first time in his life. Or to hide in his mum’s skirt like he had when he was two.

‘Was it you?’ Dad asked.

‘I didn’t see what was in it,’ Ben said.

‘What’d I tell you about stickin’ your big bib in?’

‘I don’t know,’ Ben said.

Dad was quiet then. In Ben’s experience it was never good when adults were quiet in this kind of situation.

‘I think –’ Mum said.

Dad shushed her.

‘What do you think I should do?’ he said, letting go of Ben’s collar. Ben stood up straight, avoiding eye contact with his father. There was no correct answer to this question. Ben would either suggest a punishment worse than Dad had in mind or he would suggest something easier, nicer, and his father would erupt.

Ben shrugged, concentrating on his feet. His shoelaces were grubby and splotchy. One was untied. The leather on the toe and side of his right sneaker was grey and worn from soccer. Ben closed his eyes for a moment. On the cinema screen at the back of his eyelids, he watched the last ten minutes of his life in 32x rewind, like he was scanning back over one of his movies. He wanted to reshoot every frame from the moment he entered the cabin. He wanted to stay outside, not let curiosity get the better of him. He did not want to know what was in the bag.

‘What do you think I should do about busybodies?’ Dad said sharply, lifting Ben’s chin, pressing ‘stop’ on Ben’s in-brain rewind. ‘What?’ Dad shouted again.

‘It’s not his fault,’ Mum said, taking a few steps into the cabin. Ben could see her hovering behind Dad.

‘What’s not his fault? That I can’t have a single thing to myself without someone sticking their nose into it?’

‘We sold the wreckers,’ Mum said.

Everyone was quiet. Dad blinked and straightened his body, taking in what she had said.

‘What?’ Ben asked, turning to her.

‘Dad. He sold the wrecking business.’

Ben thought about this for a second. ‘Did they pay cash?’

Mum nodded and scratched her neck.

Ben looked at Dad, who stared back. ‘Well, why didn’t –’

‘We thought you’d be upset,’ Mum said.

‘Upset?’ Ben asked. Why would she say that? Mum knew that he didn’t like the wrecking yard. It was filled with dead, broken, rusty things and, when he was there, he had to search for parts or clean the toilet or restock the drinks fridge. The only good thing about the wrecking yard was when he found something interesting, like his camera, in one of the cars.

‘Right,’ Ben said. ‘So . . . is the money . . .’ He stopped. He tried to think back through the events of the past two days but his thoughts were scrambled. He suddenly felt tired. ‘How long are we staying here?’ he asked.

‘I need to work out what we’re doing,’ Dad said.

‘. . . for the rest of the holiday,’ Mum added.

‘Yes, for the rest of the holiday,’ Dad said. ‘Get away from me. Go down the bush and play.’

Ben did not need to be told twice. He slipped past his father, around his mother, grabbed his backpack from near the door and exited the cabin. His parents began arguing. Ben walked to the edge of the steep hill and looked down through the pine forest toward the creek. He had never spent time in the bush, had never left the suburbs. He did not want to go to the creek. The wilderness was his enemy.

‘What did you do?’ said a voice from above. Ben looked up, squinting into the sun. It was Olive sitting on the lowest branch of the tree.

The hunger hit Ben again. It was late morning and his stomach ached but he knew there was no food.

‘I’m goin’ out!’ Dad stormed out of the cabin. He was carrying the sports bag.

‘Be careful, Ray,’ Mum said, following him. ‘And please make the arrangements today. I can’t stay here.’

Dad climbed into the car and slammed the door.

‘Ray?’

‘Yes, I’ll make the arrangements,’ he said through the window.

‘And get s

ome clothes for the kids!’

Dad reversed, spun the wheel and powered off up the hill, leaving them in a cloud of swirling dust.

Ben turned and, without a word, he let the trees take him. He let himself go off the edge of the slope and disappear. Down, down, down.

Ben flew steeply down, dodging thick, rough chocolate-brown tree trunks, his feet deep in pine needles. Sun lit him in sharp bursts as he thundered into the valley. The water-rush became ever louder, filling him up.

The creek emerged through the trees and Ben began to slow, digging his heels into the damp black soil beneath. He came to a skidding stop at the large mossy sandstone boulders that led down to the water. The creek was seven or eight metres wide. Sun hit the surface in patches, revealing muddy-brown rocks beneath. In the middle the rocks disappeared. Ben wondered how deep it was.

Downstream there was a small waterfall leading to a lower section of creek. On the far side, a sheer sandstone cliff soared fifty metres above Ben’s head. Fishbone ferns poked from cracks and scars in the rock. The wall ran along the creek’s edge as far up and downstream as he could see.

Thirst tore at him then. He jumped onto a boulder that was shaped almost like a pyramid and leapt from rock to rock, careful to avoid the slippery-looking patches of moss. He was halfway down to the water when he thought about snakes. They liked rocks. He had a book on snakes at home, a library book that he had never returned. (After snakes, his greatest fear was going back to the public library, in case he was arrested for theft.) Ben loved to scare himself in the comfort of his bedroom but, out here, he couldn’t shut the book and stop the fear. Nature was real and true and terrible.

He paused on a rock and looked up the hill, thinking of running back to the safety of the cabin. Which was worse? Snakes or his family? Fear told him to get off the rocks but thirst drove him down to the water. He pulled his school socks up to his knees and stepped carefully, eyes darting all around, waiting for venomous fangs to emerge from a crevice or a crack and end him.

On the Run

On the Run Two Wolves

Two Wolves Mac Slater Coolhunter 1

Mac Slater Coolhunter 1 The Fall

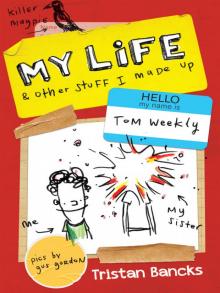

The Fall My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up

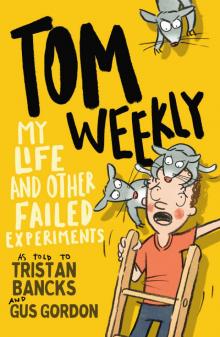

My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up My Life and Other Failed Experiments

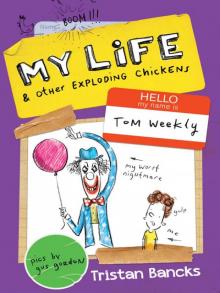

My Life and Other Failed Experiments My Life and Other Exploding Chickens

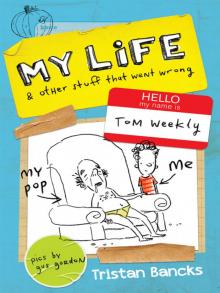

My Life and Other Exploding Chickens My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong

My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Galactic Adventures

Galactic Adventures Mac Slater Coolhunter 2

Mac Slater Coolhunter 2 My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins