- Home

- Tristan Bancks

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins Page 2

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins Read online

Page 2

She honks the horn again and shouts, ‘Come on, Tommy! Let’s go for a drive.’

I open the door a little more and call out, ‘It’s too hot, Nan. I can’t. Why don’t you come inside and rest your weary bunions?’

She honks again. If Pop were alive he’d be furious that Nan was driving his pride and joy. Pop always kept the car garaged, shining it and tinkering with the engine, but he never drove it on the road. Now that he’s gone, Nan likes to take it for a spin every now and then.

I wish Mum was home. She had to work today. There’s no way she’d let me go with Nan. My grandmother is Australia’s worst driver. Her top speed is 15 kilometres an hour. She drives so slowly that she makes time go backwards. She’s a danger to herself and others. Last time I rode with her she mowed down a stop sign, sideswiped a parked police car and smashed into the birdbath in the front yard of Mr Li’s house at number 33.

She waves me over towards the car. I shouldn’t go, but I feel sorry for her – so skinny and frail in that gigantic vehicle. I take a deep breath, hurry down the front steps and along the path. She has the Crestline sitting half on the kerb, half on the street.

‘Hello, Tommy, love. Give your ol’ Nan a kiss.’ I lean through the passenger window. She looks like a little kid at the wheel. She has to sit on three fat phone books from 1984 just to see over the dashboard. Nan climbs off the books and shuffles across the seat so I can kiss her on the cheek. Her skin is soft and wrinkled and sweaty. The car’s engine rumbles and grumbles and burbles. Steam hisses from the cracks around the edge of the bonnet. Pop must be spinning in his grave.

‘You really shouldn’t be driving, Nan,’ I tell her.

‘Why not?’

‘You don’t have a licence.’

‘When I was a girl, you didn’t need a licence. I’ve been driving since I was seven years old.’

‘I didn’t know cars were invented then.’

‘Don’t be a smartypants,’ she says. ‘Back in my day, I could reverse a tractor through a flock of sheep blindfolded. Don’t you trust me?’

No is the answer, but she gets really mad when I question her driving skills.

‘Yes, Nan, I trust you. It’s just that … I’ve got homework. I –’

‘Rubbish. You’ve never done homework in your life. Now get in. I’ll buy you an iceblock and take you to the swimming pool.’

Sweat runs in ticklish rivers down the sides of my face. The sun grills the skin on my forehead like cheese on toast. I think about her offer. I weigh up the fear and embarrassment of being in the car with her against the sweet relief of the pool and the iceblock.

I open the passenger door and slide in.

‘That’s my boy,’ she says, grinning and revving the engine twice.

I reach for my seatbelt and try to find the socket to slot it into, but it’s not there.

‘Must have fallen down the crack between the seats, love. Not to worry. Off we go.’

She jerks forward and I’m thrown back against the seat. I plunge my arm down into the seat crack. I find an old Mintie with sand all over it and a ‘One Penny’ coin before I find the socket for the belt. I pull it up, slot it in and tighten it until my guts are about to squeeze out of my ears.

‘You have nothing to worry about,’ she says.

She stomps on the accelerator, the tyres squeal, and we shoot out from the kerb. A car going by honks its horn and swerves, narrowly missing us.

Nan honks back. ‘Nincompoop!’ she screams. ‘Sorry about that, Tommy. There are some crazy drivers on these roads.’

I pull my belt tighter and the car settles into Nan’s 15-kilometre-an-hour crawl up the hill.

‘Nan, the pool’s at the other end of the street.’

‘I thought I’d get your iceblock from Papa Bear’s. You can eat it on the way. How does that sound?’

‘Thanks, Nan,’ I say as we continue to climb. Papa Bear’s is the shop up the hill on the corner of our street. My legs are sticking to the old vinyl seats in the heat, but it’s quite nice going this speed. You notice stuff you wouldn’t normally. Like that cat that just overtook us.

Oh no. My stomach sinks.

Brent Bunder and Jonah Flem are waiting to cross the street with their bikes about 40 metres up the hill. I slump down in my seat so I can’t be seen.

‘What’re you doing?’ Nan asks.

‘It’s comfy like this,’ I tell her. ‘Cooler.’ I look up and notice that the clouds are moving faster than we are.

‘Can you go any slower, Grandma?’ Jonah calls out as we drive by.

‘Shut your gob, pipsqueak!’ Nan screams. ‘Respect your elders.’

Brent and Jonah laugh.

‘Hey, is that you, Weekly?’ Brent asks.

I slide down further into the seat.

‘Hey, Weekly!’ he calls.

The two boys pedal slowly alongside the car, looking down at me.

‘Nice Sunday drive, mate?’ Jonah asks. ‘Why don’t you just walk? It’d be faster.’

Nan swerves to the right and bumps one of their bikes. I sit up and look back to see Jonah checking his front wheel. ‘Hey!’ he shouts. ‘You’re a danger to society, lady!’

‘Your face is a danger to mirrors!’ Nan shouts back, peering through the steering wheel as we crawl up the hill. ‘That showed them.’

‘Nan, you’re not really supposed to knock kids’ bikes.’

‘They’re not kids. They’re cane toads. There’s no law against squishing a couple of cane toads, is there?’

I shrug. Flem and Bunder are kind of cane toad-ish. But the police might not see it that way if they report her. A few minutes later we roll up outside Papa Bear’s. Nan slams into the rear bumper of the car parked out front, then rolls back downhill a few centimetres.

‘There we go,’ she says. ‘What do you want, love? A Bubble O’ Bill?’

Nan knows that I love Bubble O’ Bills more than life itself. Especially on a flesh-meltingly hot day like today. I nod and grin.

‘Two Bubble O’ Bills coming right up.’ She grabs her purse, climbs down off the phone books, exits the car and slams the door. She slams it so hard that the car wobbles from side to side. There’s a screeking sound of metal on metal, the suspension groans, and the car starts to roll slowly backwards.

‘Nan!’ I shout, but she’s shuffling along in front of the car now and doesn’t hear me.

I look to the dashboard and see a handle that says ‘Park Brake’ in faded white lettering. I reach across and yank it hard. The handle heaves back towards me … and snaps off in my hand. I scream and throw the handle into the back seat.

‘Nan!’

She disappears inside the shop and I’m picking up speed. I’ve rolled about five metres down the hill and I’m heading towards a silver hatchback parked on the kerb. I could open the door and jump out, but I’d hit the gutter pretty hard.

I peel my sweaty legs off the seat and slide across until my hip hits the pile of phone books. I jerk the wheel to the right in a desperate attempt to miss the parked car. The back of Nan’s car veers out into the road and another car swerves around me, the driver slamming his fist on the horn. I’m heading diagonally across the street now, so I pull the wheel back towards me to stay on the left side of the road.

I’m really moving now. I chuck the phone books onto the passenger floor and slide behind the wheel. I’m looking back over my shoulder and trying to steer, but I haven’t driven a car recently – or ever – so it’s a bit difficult. My feet are tap dancing, trying to find the brake pedal. It must be down there somewhere.

Jonah and Brent are in the middle of the road.

‘Get out of the way!’ I shout out the window. I look for the horn and slam my fist down on the big ‘Ford’ logo in the middle of the steering wheel.

Waaaaaaaarp! The horn blurts.

I look back through the rear windscreen. Brent and Jonah look up at the car speeding towards them. We all scream.

Click here to see

what happens next.

‘Mum, where’s my school shirt?’ I yell from my room.

‘The same place it is every day,’ she calls from the bathroom.

‘Where’s that?’

‘In your drawer.’

‘It’s not there.’

‘Have you looked?’

‘Yep.’

Mum growls, but it doesn’t worry me. We do this every day. My school shirts always go missing. I think she kind of enjoys it. Like a game of hide-’n’-seek. Adults don’t get to have fun very often.

‘Well, have another look!’ she shouts. ‘I find opening my eyes works quite well.’

‘My eyes are open.’

‘Will you two be quiet?!’ my sister, Tanya, screams from her room. ‘I’ve still got five minutes till I have to get up. I need my beauty sleep.’

‘You’re gonna need a lot longer than five minutes,’ I tell her.

‘Shut up, Tom.’

‘If I come in there, I’m just going to find it immediately. Then I’ll be annoyed for the rest of the day,’ Mum says. ‘So have another look, Tom.’

‘It’s not here!’ I insist.

Another growl.

Footsteps.

Mum walks into my room.

I’m lying on the bed in my pyjamas reading a Tintin book called The Broken Ear.

She stops in the doorway. ‘What are you doing?’

‘Reading a Tintin book called The Broken Ear.’

‘Why are you reading?’

‘I thought you liked it when I read?’

Mum rubs her forehead with the palm of her hand and sighs loudly. This is never a good sign. ‘I do, but you’re supposed to be looking for your shirt.’

‘I can’t find it.’

She walks over and opens my top-right drawer. ‘Look what I found!’ she says, holding up a school shirt.

‘Oh, thanks.’

She stands there staring at me. I appreciate her finding the shirt, but I’d kind of like to be left in peace now.

‘Did you even look in this drawer?’ she asks.

‘Nope.’

‘Why not? It’s clearly labelled with the words “school shirts”. See? Right here.’ She points at the label a little too aggressively.

‘Oh, yeah,’ I say.

‘This is where your school shirts go.’

‘I forgot.’

‘Aaaaaaaaaaaargh!’ she screams.

I sit up. Screaming is Mum’s little way of telling me that she’s feeling a wee bit frustrated.

‘You’ll actually be the death of me, Tom Weekly.’

‘Geez, it’s just a shirt.’

‘Put. It. On,’ she hisses and slouches out of the room.

Sometimes she gets like this in the morning – touchy for no reason at all.

I put my shirt on and look in my drawer, scratching my bum.

‘Mum!’ I call out.

‘Yes?’ she shouts back, her voice trembling.

‘Do you know where my shorts are?’

I have something to admit. I’ve been suffering from writer’s block. That’s where you can’t think of anything to write, so you just sit there staring at the page like a numpty. I didn’t think writer’s block was a real thing until recently. I thought it was something writers made up so they didn’t have to work, which is pretty genius of them, really. I wish teachers would invent ‘teacher’s block’, where they couldn’t think of anything to teach so they’d just sit there, drooling and staring at the whiteboard six hours a day. And I wish Mr Skroop, the Deputy Principal, would come down with ‘Skrooper’s block’, so he wouldn’t be so … Skroopy all the time.

But writer’s block is no joke – my brain is officially dead. Zombies wouldn’t bother eating it. Even for an entree. The worst part is that I know why I have it, and I know how to cure it. But the solution could mean the end of my writing career.

It’s Sunday morning and I have been lying on my bed, staring at a blank notebook for hours. Yesterday … the same thing. I can’t go on like this. I owe it to the world to continue to share my gift for telling stories about scabs and missing body parts and sloppy food and head lice.

I lean over to the bookshelf next to my bed. I reach behind the first row of books and feel around until my hand rests on Natrix’s Big Book of Magic. It is a hefty tome with a carved wooden cover, about ten centimetres thick. I lift it out and look at it for a few seconds, my heart hammering away. I open it. Inside, there is a rectangular hole carved within the pages, and inside that is a little green box. I take out the box and rest it in the palm of my hand.

Don’t do it, some part of me whispers. This is wrong.

I lift the lid of the box, revealing tiny crystals and shells and the tip of a magpie feather. I remove the false bottom of the box, and underneath lies the answer to my problems. It seems to pulse with a green, magical glow. My fingers are magnetically drawn to it. I reach in and take out a single, gnarled toenail. My very last one. I hold it up to the light from my reading lamp above my bed, and I actually salivate.

I have never admitted this to anyone but … all of my stories have been written while chewing on my grandfather’s toenails.

There. I’ve said it.

People always ask me where I get my insane story ideas. Well, now you know. I’m not proud of it. I mean, it’s one thing to chew on your pop’s toenies when he’s alive. Quite another thing to do it after he’s, you know … not.

I first got a taste for toenies when I was two years old. My fangs were coming through and I’d lost my teething toy, so I started jawing on Pop’s toenails to ease the pain in my mouth. Mum tried to stop me but Pop thought it was hilarious, a story he could tell his mates.

‘Leave the boy alone,’ he’d say. ‘He can’t help being part dog.’

Pop would tell me stories while I chewed on his toenies. And even when my teeth came through I didn’t stop. I used to bite those knobbly yellow husks right off his foot. I loved listening to Pop’s tales about epic thumb-wrestling contests in the trenches during the war and billycart crashes and heroic efforts on the cricket pitch when he was a kid.

It kept going till I was about five, when Mum told me I wasn’t allowed to do it anymore. She said it was unhygienic and weird.

But it was too late. I was hooked. Pop never wore shoes, so I could always tell when he had a ripe nail on the go. I couldn’t wait to snip it. It must have been my ancient hunter-gatherer instincts kicking in. I started chopping Pop’s nails with regular clippers for a while, but the nails were too tough. I went through seven sets of clippers in two years.

So I put together a little kit – tin snips, a hacksaw, a rusty metal file and a small set of chisels. I would visit Pop every few weeks, and he’d tell me stories while I worked. When I was finished, I’d put the toenies into a plastic sandwich bag and take them home to snack on.

Then, the Christmas I turned nine, I read Paul Jennings’ book Unreal and decided to start writing my own stories. On Boxing Day morning I sat at the dining table with a Santa hat on, ready to write, but my mind was blank. Without thinking, I cracked open my bag of toenies – a toenie always makes a man feel better – and my pen started moving. It felt like I was possessed with the power of all the tall tales that Pop had told me over the years while I’d been gnawing on his feet. I wrote and wrote all day long and into the night.

Then, a little over six months ago, as I sat on Pop’s rickety footstool in the nursing home, I sawed off his last toenie. I didn’t know at the time that it would be the last one. Pop prattled away about his battles with the other nursing home inmates, the disgusting meatballs he was served for lunch and his latest plan for escape. With one final stroke of my little hacksaw, the nail fell from Pop’s foot and skittered across the linoleum floor. It was magnificent – one of the biggest toenies I had ever seen – so I picked it up and dropped it into the sandwich bag with the other nine delicious nails. I quickly said goodbye, disappeared into the hallway and rushed out the front door of t

he nursing home.

As soon as I was back in my bedroom, notebook ready, pen in hand, my greedy fingers delved into the bag, chose a medium-sized toenie and jammed it into the corner of my mouth. I began to chew and the words started to flow.

I know it’s sick, but I can’t help it. When you get a taste for toenies at an early age, it’s very difficult to give up. I feel most alive when I’m nibbling on one. Pop’s toenails had played football for the 1959 New South Wales under-17s rugby squad. They had carried him down the aisle when he got hitched to Nan. They had fought for their country in Vietnam. They told better stories than any book.

They’re dangerous, too. If you aren’t careful and you swallow one whole, it can slit you right open. I once devoured a toenie and it scratched me all the way down through my throat, stomach and intestines for two days. I was worried it’d get stuck inside … but it came out alright. The pain was mind-boggling.

If only I’d known that we wouldn’t have Pop with us much longer, I wouldn’t have let my supplies run down. He died so suddenly six months ago, in the lead-up to Fast Eddie’s Hot Dog Eat. I only had 20 toenails in storage and I’ve been writing so much I’ve eaten 19 of them.

I know exactly what you’re thinking. I’ve already considered farming other old people’s toenails. Nan’s aren’t bad but they’re too small and dainty, and they take forever to grow. They don’t snap between your teeth, and she bathes so regularly that they have no smell. The flavour is disappointing, too, like a pretzel without salt or a cupcake without icing. They’re just too … nice. Edible but forgettable.

So, here I am, staring at the last toenie glistening in the light of the reading lamp. It is shaped like a crescent moon and coated in a thin film of soil or yeasty toe jam, I’m not sure which. It seems to stare back at me, like it can see right into my soul. I already know what it will taste like – sweet and savoury, like a block of Vegemite chocolate. I could get two or three days out of it if I’m careful. But it’s the last thing I have to remember Pop by. Do I really want to devour the last trace of my grandfather?

On the Run

On the Run Two Wolves

Two Wolves Mac Slater Coolhunter 1

Mac Slater Coolhunter 1 The Fall

The Fall My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up

My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up My Life and Other Failed Experiments

My Life and Other Failed Experiments My Life and Other Exploding Chickens

My Life and Other Exploding Chickens My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong

My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Galactic Adventures

Galactic Adventures Mac Slater Coolhunter 2

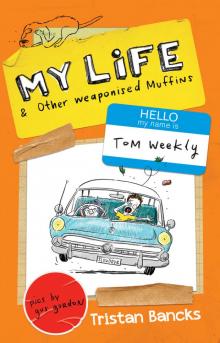

Mac Slater Coolhunter 2 My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins