- Home

- Tristan Bancks

Two Wolves Page 14

Two Wolves Read online

Page 14

He listened for the creek. As they had walked up the steep dirt road from the cabin he had listened for it till the last. Then the umbilical cord had been cut and the sound was gone. Just Ben and Olive. Now he thought he heard it again, like the distant sound of the ocean in a shell. But the sound was a car. It appeared around the big bend a couple of hundred metres up the road. A small yellow hatchback filled with passengers. It had ‘P’ plates on the front and, as it passed, someone screamed at them from the window.

‘Have some water,’ Ben said, bending down to offer Olive the dregs of the bottle he had found in the cabin.

She did not respond.

They waited a long time, maybe twenty-five minutes, for the sound of another engine. But what turned the bend was a motorbike, not a car, and it sped past them down the hill and away.

A week earlier Ben would have been beaten by this, would have been angry and frustrated and scared. He would have thought that the world was out to get him, but now he did not expect so much. Things could not rattle him so easily. Maybe not even death. He would not get carried away with things, good or bad.

After ten minutes another engine, louder, lower. A truck, Ben was sure. In his clouded, tired mind he calculated that there might only be two seats in a truck and some part of him gave up hope but he looked down at Olive and he knew that he had to stop the truck.

It rounded the bend, a semitrailer with a green cab and dozens of long logs on the back. Ben waved his arms wildly.

‘Help!’ Ben called. ‘Stop!’

Olive was startled by the shouting and tried to stand but she faltered and dropped to her knees. Ben wanted to comfort her but he knew that his job was to get them home, to get them to Nan’s. The truck moved past them and there was no way the driver could not have seen them. Ben watched the back of the truck recede, but still anger did not rise up in him.

He coughed heavily. His lungs ached.

Red lights and a deep groan a hundred metres further on, before the steep hill that led to the faraway bend. The truck’s red brake lights. Maybe just slowing for the hill, Ben figured, but then it pulled to the side, rocks kicking up, indicator on.

‘This is us.’ Even as he said the words, Ben did not believe them.

Olive didn’t seem to hear him. She was lying down again so he scooped her off the ground, balancing her across his arms as he walk-ran toward the truck, which was still slowing, half-on, half-off the road. Every molecule of energy left in his starving, exhausted, bleeding body went into that run.

He reached the truck as it finally pulled up with a sssss and a crunch of tyres on gravel. He ran alongside the truck and the driver watched him in the dirty passenger-side mirror. The door popped open and swung over Ben’s head. The driver – neatly shaven, brown shirt, sunglasses, kind of old-fashioned-looking – met them with a smile. He had good teeth, Ben noticed. He would have thought that truck drivers didn’t brush their teeth very often, but this one did.

‘Thank you,’ Ben said.

The driver looked down at them, at their dirty, ragged clothes. ‘You lost?’

‘Sort of,’ Ben said.

He listened. With every ring he clutched the phone more tightly. Why wasn’t she home? Nan never went out.

The payphone was in a timber bus shelter crammed with backpackers sitting on their luggage. Cars crawled by on Kings Bay’s main street. Olive sat on the ground, eating an energy iceblock from the chemist, listless.

The truck driver had let them out at the hospital on the edge of town, had told them that Olive needed to see a doctor. ‘I’ll come in with you,’ he’d said over the engine noise, ‘make sure she’s all right.’

‘No,’ Ben had replied, ‘We’ll be okay. It could take hours, slow you down. Thanks, though.’

The driver had given him a long stare and looked down at Olive. Ben had slammed the truck door and the driver sat there idling for a moment. Ben wished him away and, eventually, the truck gave a low moan. Ben had waited till it was out of sight before turning away from the hospital and walking into town, Olive on his back. He couldn’t take her for medical help because he would have to give their names. They might be recognised. A couple of people had looked at them strangely, had pointed, and Ben wondered if they had been on the news, if they were ‘Wanted’ or ‘Missing’ or if they just looked funny.

They showered at the surf club, and Ben bought new clothes and a bag full of different medicines from the chemist. He had tried to heal her and she had eaten. Not much, but she had.

The phone continued to ring. He wondered if the phone might be tapped, if he was putting Nan in danger. He remembered, from a movie, that you could tell if a phone was tapped: you’d hear a small beep or click a few seconds after the call began, when the recording started. But was that a really old movie? He couldn’t remember.

Finally, after almost a minute, ‘Hello?’

‘Nan. It’s Ben.’

He did not hear a click or a beep but he still didn’t say much. He did not tell her everything. Just that they were alive, that they would see her soon.

And then the question that he was most afraid to ask: ‘Have you seen Mum and Dad?’

She paused for a long time before she answered.

At the Visitor Information Centre, Ben bought two tickets for the 4.30 pm bus from a lady with long white hair. Her name tag said ‘Julie’. She looked at him suspiciously, and at Olive.

‘Where are your parents?’

‘In Sydney. That’s where we’re going. We’ve been staying with our aunty,’ Ben said. ‘In Kings Bay.’

The lady did not believe him. ‘Is your aunty around?’

‘No. She had to go to work,’ Ben said.

He was not a good liar. He knew that. He was good on paper, in his movie scripts, but not when someone was looking at him. The lady suggested he and Olive take a seat inside and she gave them paper cups of water and Minties. He was glad to have someone look out for them but he watched her carefully and listened to her phone calls, scared she would call the police. Would other customers recognise them? How many people knew that they were missing?

The journey down the coast was slow. Olive fell asleep the moment they sat in their stained, threadbare seats, second row from the front. He watched her carefully, wondering if he had done the right thing by not taking her to the doctor.

‘Going home,’ he said quietly. She sucked her thumb, cuddled Bonzo – dirty, ragged, weary.

Ben fought to stay awake, sipping a steaming cup of milky coffee he had bought from a machine in the Information Centre. He missed the sound of the creek, missed the feel of it, even though he was thankful to be somewhere warm and comfortable. He closed his eyes and tried to hear that shhhhh in the white-noise whir of tyres on wet road.

‘Click flutter, flutter click,’ said a woman behind them, over and over again, her voice low and unnerving. Ben peered through the gap between the seats. She had white-blonde hair, messy lipstick. She bit her nails loudly – click tick tick – repeating the words ‘click flutter, flutter click’ again and again.

Across the aisle was a small, straight-backed woman wearing fluorescent yellow jeans and zebra-print boots. Her feet did not touch the floor of the bus. Behind her, leaning against the window, was a man with a skeletal face and wild green eyes that shone bright in the passing headlights. He turned to Ben and asked him something but Ben could not hear the words. Ben smiled, tried not to look scared and turned away.

When the coffee had gone through him, he went to the toilet at the back of the bus. He took Olive with him, guiding her unsteadily up the aisle.

There were about twenty passengers. Most of them looked broken in some way, Ben thought. They wore the scars of hard lives in their faces and in the way they sat. When Ben was little, he hadn’t known that people could become broken. Toys and plates and windows, he knew, but not people. Now he knew th

ey could. Not just hairline fractures but compound breaks, where the bone pushes through the skin. Like when Olive broke her arm when she was four. Ben wondered if he would become broken like that some day.

Hours later, when everyone else on the bus was asleep, Ben drifted into an unsettled nap. He woke regularly to check on Olive, expecting to find himself leaning against the roots of a fig tree or lying on a rock or flat against cabin floorboards.

Olive woke around midnight.

‘Can I have some water?’

Ben gave her some. She lifted her head from his shoulder and drank slowly.

‘I’m hungry.’

He had not heard her say that in a couple of days. He reached for his school backpack, packed with food. She nibbled a rice cracker for a few minutes, then asked, ‘Where’s the bag? The bag of money?’

Ben’s heart thumped.

He bolted down the alley, battered school backpack on his front, Olive on his back. Morning light. Litter everywhere. Fences to the right and a wide concrete drain to the left. He slowed, looked both ways, took a deep breath and shoved through Nan’s squealing back gate into the long grass of her yard. Golden, their three-legged dog, barked angrily and ran at them.

‘Let me down,’ Olive said, and Golden whined in a happy way. Ben let Olive down gently. She kneeled. Golden licked her face, then ran across the yard like a maniac, doing circuits around the clothesline, past the tumbledown chicken pen and the old, white car wreck that Dad had brought home when he was seventeen.

‘Shh! Shhhhhh!’ Ben said to Golden, trying to calm her. He pushed the gate shut and walked up to the house. Peeling paint. Light-blue fibro. He climbed onto the timber back veranda, avoiding the rotten stairs. He knocked quietly and heard the familiar squeak of Nan getting up from her armchair. Then the shuffle of slippers on carpet before her silhouette appeared behind the sheer white curtain.

She slid the curtain and door aside, and she grabbed him and hugged him and cried.

‘You two,’ she sobbed. She was wearing one of her brightly coloured kaftans. Pink and purple. Ben reached down to help Olive onto the veranda and she squeezed between Nan and Ben, making a sandwich.

‘Come on,’ Nan said. ‘Inside.’ She looked to the houses on either side and over the back fence, then slid the door shut and drew the curtain.

It was bright and warm inside, like always. Nan didn’t like it when people turned lights off in her house.

‘Did you see the police out front?’ she asked.

‘I think so,’ Ben said. ‘But I think they were in a regular car. A black one. That’s why we came the back way. Are Mum and Dad here?’

‘They left a couple of days ago. They’ll be back this morning. Soon, probably.’

Ben’s stomach dropped. Nan squeezed them into her so tight that the three of them became one, like Ben and Olive could never go anywhere again.

‘I knew you were alive,’ she said.

Ben felt the creek rush through him for a moment.

‘What happened to you?’ Nan asked. ‘You both look so skinny and horrible! What have you been eating? And your hair’s too short, Ben. What have they done to you? Let’s run a bath.’

‘Ben lost the money!’ Olive said, dropping the words into the room.

Ben shot her a glare. Nan stopped and looked at him through her watery hazel eyes.

‘What do you mean?’ she asked.

‘Mum and Dad, they –?’ Ben began.

‘I know what they did,’ she said.

Ben took a breath, ready to say what he had rehearsed, but he had been caught off guard by Olive.

‘I lost the money,’ he said. ‘It was in a bag and we were in a bus shelter and we got on the bus and there were heaps of people around and I must have left it. We realised on the bus in the night but we were already so far down the coast and someone would have taken it, I know, and Dad’s going to be so angry. I don’t want him to come back here. Can you stop him coming back?’

He buried his face in Nan’s shoulder so she could not look at him and she put an arm around him. He continued babbling about how he didn’t mean it, that he was stupid, that he had looked after the money all those days, carrying it up the creek and then, at the end, when there was no danger, he had left it. Saliva and snot dripped from his face onto Nan’s shoulder and he wiped it off and rubbed it on his jeans.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said. She looked him in the eye. ‘Don’t worry. Did you mean to leave it?’

Ben thought about the question and then shook his head.

‘No, of course you didn’t,’ she said. ‘Well, don’t worry. It’ll be okay. We’ll work something out. At least you’re back. You’re much more precious than a bag full of money.’

Ben wanted to believe that.

‘Come,’ Nan said. ‘Come and eat. You must be starving.’

They sat at the kitchen table and she made them steaming-hot tea. Ben did not like tea but he drank it. Nan made him toast with Vegemite and sugar toast for Olive. She cooked poached eggs with lots of salt and tomato sauce and she put the tall yellow biscuit barrel on the table in front of them along with glasses of milk. Olive did not eat much and Ben felt sick after the eggs. He tried to keep eating to make Nan happy but the hole inside him was not as big as it used to be.

Ben told her everything they knew. About the night the police came and the raft and the helicopter and the storm and the night he thought Olive might die and finding the cabin again and hitchhiking and the bus trip. Everything. Almost everything.

Nan listened and nodded and occasionally excused herself, going to the front window in the lounge room, peering through the curtains.

When Ben finished, Nan led Olive up the orange-carpeted hall to the bathroom. He heard the bath running and Nan and Olive chatting. He had always liked being at Nan’s more than being at home. He took off his new shoes and peeled off the socks. They ripped at half-formed scabs on his feet.

‘I’ll make soup for lunch,’ Nan said, coming back into the kitchen.

Ben watched her chopping onions, thinking how easy food seemed now. Food had been so hard out there. Everything had been hard. He wanted to always remember.

She wiped her eyes with her wrist and looked at Ben in a funny way, scraping onions off the board into a pot.

‘What?’ Ben asked.

She took another onion and peeled it.

‘I want to tell you something,’ she said.

Ben waited.

‘They’ll be back soon, but there’s something you should know first.’

Ben could feel the food and tea wrestling each other in his belly.

‘It’s about your grandfather.’

Ben liked stories about Pop.

‘He was a crook,’ she said, wiping onion tears. ‘He was a criminal, a scammer.’

She chopped slowly now, looking to Ben for his reaction. ‘That’s why he built that cabin. A place to hide.’

Ben started to say something but he stopped. He was shocked but he also felt as though he had somehow known this all his life. He thought of the stuff they had hauled out of the cabin – the gun, the traps with tough steel jaws and the safe. He thought of the story about the wolves in Pop’s old notebook. He thought of his uncle giving Dad the bag.

‘Is Uncle Chris dodgy too?’ Ben asked.

‘I don’t know what your Uncle Christopher is up to.’

‘Do you think we have convict blood? Maybe we can’t help it. The Silvers, I mean. Was Pop’s dad a crook?’

‘I don’t know. Probably,’ she said. ‘Your grandfather nearly got me killed a thousand times. I hated it. And now your useless father is doing the same thing. Promise me something, Ben . . .’

He knew what she was going to say. She scraped another onion into the pot and pointed the knife at him.

‘Don’t turn out lik

e your grandfather.’

Golden barked and the gate in the back alley squealed open. Ben looked out the window, adrenaline churning through him.

‘That’s them,’ Nan said. ‘Come. Into my room. Let me deal with him.’

She gave Ben a push in the back, ushering him down the darkened hall. She stopped at the bathroom. ‘C’mon, out you get,’ she said to Olive. ‘Whoops-a-daisy.’

‘I don’t want to get out!’ Olive protested.

Ben heard Dad’s footsteps on the back veranda.

‘Who is that? Is that Mummy?’ Olive asked.

‘Shhh,’ Nan said, wrapping her in a towel and guiding her down the hall to Ben, who was standing in the bedroom doorway. ‘I’ll check, love. One thing at a time. Just let Nanny sort something out and then you’ll be able to give Mum a big hug, okay?’

Olive dripped on the carpet and shivered.

‘Nice and quiet, you two. We’ll surprise them.’ She winked at Olive.

‘Is Ben going to get in big trouble for losing the money?’ Olive asked.

‘Shhh. That’s a good girl.’ Nan pulled the door closed just as Ben heard the back door slide open.

‘Hello?’ It was Mum’s voice.

‘Coming,’ Nan said, slippers shuffling double time up the hall.

The moment Ben heard his father’s voice in the kitchen he heard another noise at the front of the house. A heavy knock on the front door.

Then footsteps. Fast. Down the hall. Bedroom door open. Mum. Short-cropped hair. Dark circles under her eyes.

Ben had planned to be strong, to not show any emotion. That was before he saw her face fall apart and the tears falling from her eyes. She looked as though she had been out in the wild too. She hugged them so tight Ben thought his ribs might break.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she whispered and it seemed to Ben that her whole body bucked with the crying and the grief and the happiness. He had never loved and hated a hug so much in his life.

On the Run

On the Run Two Wolves

Two Wolves Mac Slater Coolhunter 1

Mac Slater Coolhunter 1 The Fall

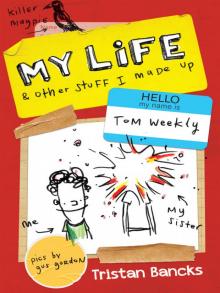

The Fall My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up

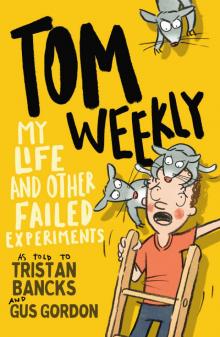

My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up My Life and Other Failed Experiments

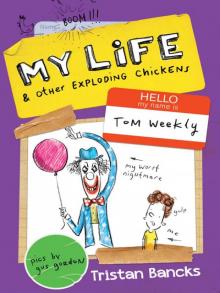

My Life and Other Failed Experiments My Life and Other Exploding Chickens

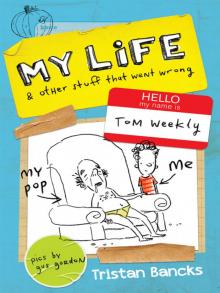

My Life and Other Exploding Chickens My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong

My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Galactic Adventures

Galactic Adventures Mac Slater Coolhunter 2

Mac Slater Coolhunter 2 My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins