- Home

- Tristan Bancks

Two Wolves Page 12

Two Wolves Read online

Page 12

Ben walked out from beneath the tree, toward the creek. He left the bag of money lying on the ground. Was that why he had stopped Olive? Was it to protect his parents, his sister, himself? Or was it to protect the money? Maybe. He hoped not. But maybe. It was a lot of money. The police would take it away.

‘Which way should we go?’ Olive asked.

Ben looked down into the red-stained creek. The red was from a plant, he thought. Too much for it to be blood. But still it made him feel sick. He looked upstream, toward the not-knowing place, where he had been at the mercy of his parents. A place he and Olive could not go back to now. He looked downstream into the unknown shadows and shapes created by the trees on the bank. The creek twisted and turned into a gnarled tunnel. He turned and looked into the savage sprawl of wilderness behind him and on the other side of the creek. A place to become lost.

For the first time in Ben’s life, he could choose to do whatever he liked, go wherever he wanted – and he felt stuck.

‘I’m hungry,’ Olive said.

‘What do you think we should eat?’ Ben asked.

‘Do you have any chips?’

Ben looked at her. ‘No. I don’t have any chips.’

‘Crackers?’ she asked.

Ben sat down at the creek’s edge and hung his feet off the steep, muddy bank. He peeled his wet shoes and socks off. The creek was about five metres wide here with dense bush on the far side. Back near the cabin it had been wider. How far downstream had they floated in the night? He had stayed awake for hours and couldn’t remember when he had fallen asleep but he did know that the creek had been running quickly. He let his backpack slide off his shoulders.

The day was starting to warm and, in the sunny patches, steam rose from the moist, damp earth around him.

‘What have we got?’ Ben asked.

‘Huh?’

‘In your pockets and stuff. What have you got that could help us?’ Ben unzipped his backpack as he spoke. He placed his wet video camera on the flat sandstone rock next to him. My Side of the Mountain, his knife and soggy notebook. A random array of pens, pencils, textas and pencil shavings from the zipper bit at the front.

Olive laid Bonzo down, waterlogged and pathetic.

‘Is that all you’ve got?’ Ben asked.

She stuck her bottom lip out, nodded.

Ben produced a soggy mess covered in cling wrap from the bottom of his bag. He placed it in the sunshine next to the other things. A long-forgotten sandwich. Not in the traditional sense. It was more like a handful of mushy porridge with bright blue and green spots.

‘What is that?’ Olive asked.

‘Sandwich. It’s a bit old.’

‘I am not eating that. I would rather die.’

He shoved it at her face.

Olive squealed and ran.

Mouldy sandwiches were one of Ben’s favourite things in the world. He and Gus had a competition running to see who could find the bluest sandwich in the bottom of their bag. This one was a contender. Ben was annoyed that Gus was not there to see it and part of him, down near his belly, sank. His old life felt as foreign as this place now.

It was the only food they had and he knew they may have to eat it if they didn’t find anything else soon. He pressed it flat and tried to make it square, so that it resembled a sandwich again. Maybe it wouldn’t be too bad once it was sun-dried.

‘I’m hungry,’ Olive said again.

‘Do you think telling me fifty million times is going to make food magically appear?’

Olive looked hurt. Ben felt bad for snapping. He heard his mother’s voice in his mind: ‘She’s only seven. Give her a break.’

‘Well,’ Ben said, ‘maybe we should go look for food.’ He turned to the trees behind him.

Stay where you can hear the creek, he thought. Don’t leave the creek.

‘Do we have any food?’ Olive asked. ‘What about in that bag?’

Ben looked over at the bag of money lying beneath the tree. He laughed. They had so much money. Ben had once heard Mum telling Dad in an argument that ‘money doesn’t buy happiness’. He had thought this strange at the time. Of course money could buy happiness. But now he knew.

‘There’s no food in the bag,’ Ben said.

‘Are there any shops?’ Olive asked.

‘No,’ he said. ‘There aren’t any shops.’

Ben felt the force of the wild all around them. In the cawing of crows high in a dead tree and the relentless chirping of insects and the silence of the big blue sky. He was not sure if the force was for or against them. But it was there.

‘Do you think Aborigines in the olden days ever ran out of food, like us?’ Olive asked.

Ben looked around. Yams. He had heard of people eating yams. Maybe he would find a yam.

‘Do you know what a yam looks like?’ he asked her.

‘A man?’

‘A yam.’

Olive did not respond.

Sugar ants. He had seen a show once where a guy ate sugar ants right out of the palm of his hand. Ben looked at the ground next to him. There were ants but he didn’t know which was a sugar ant and which was just a mean, biting ant.

‘What about bush tucker? Do you know anything about that?’ Ben asked.

‘Is my vegie patch bush tucker?’

Ben looked at her.

‘I grew some really good radishes. Maybe we’ll find radishes!’ she said.

‘Maybe.’ Ben hated radishes. He opened the copy of My Side of the Mountain, gently peeling the wet, stuck-together pages apart, trying not to tear them. Sam Gribley had survived a year in the wilderness by himself.

‘He found heaps of food, didn’t he?’ Ben said. ‘Berries, acorns, deer. Remember when he ate a deer and used deer fat for his lamp?’

‘That was disgusting. We can’t eat a deer!’

He wondered if there were even any deer around here. Sam Gribley had been in the Catskill Mountains in New York. Ben wondered if any of the same things grew here. He was pretty sure there would be no raccoons, weasels or falcons.

‘Nothing we ever learned at school can help us here,’ he said.

‘An Aboriginal man came to my school and showed us how to throw a boomerang once.’

‘That’s helpful,’ Ben said. ‘Do you have a boomerang?’

‘No,’ she said quietly.

They sat for a few minutes. Cawing and buzzing all around. The flow of the creek.

‘Sam Gribley is a survivor. You could drop him in the desert or on the moon and he would find something to eat. We have to think like that, too.’

‘Is Sam Gribley real or made up?’ Olive asked.

Ben put his wet shoes back on without socks. ‘Doesn’t matter,’ he said. He headed for the giant tree, where he had seen the hard green fruit lying on the ground. Olive followed.

He picked up one of the pieces. ‘Wonder what these are.’

‘Figs,’ she said.

He looked at her.

‘It’s a fig tree,’ she said, as though he should know.

He flicked open his knife and sliced off a piece of the fruit. He put it into his mouth. It was bitter and crispy. He spat it out, offered the fruit to her. She put her thumb in her mouth, cuddled her dirty, stuffed rabbit and shook her head.

‘C’mon. We’re going to find food,’ Ben said. ‘There must be heaps out here.’

Imagining that your parents were dead was not a nice feeling, Ben found. Particularly when it was dark and mosquitoes were biting and you were sitting on the ground against a tree and you had no fire and your belly was empty and your little sister Olive had been crying and angry at you and you were angry at yourself.

Life had always seemed hard at home. He had to walk to school and he only got to order lunch once a week and he had to wash the dishes sometimes

and put the bins out and feed the dog every day and shower and remember to brush his teeth. He only got eight dollars pocket money and he had to eat potatoes for dinner even though he didn’t like potatoes, except when they were in chip form.

But then, at the cabin, things had seemed harder, with the not-knowing and Dad being more nervous and angry than ever and Ben trying to find out why there was a bag full of money hidden in the roof. Then Mum and Dad locked them in and the police came late at night and they had to escape on the raft.

But now, lying here in the pitchy dark on the damp ground and feeling the deepest fear he had ever felt, he would have done anything to be at home or at the cabin. The cold swept up from the creek, blowing through him, eating his muscles, clutching his bones.

He listened. The shhhhh of creek calmed him a bit but he was not listening for the creek now. He was listening for the sounds beyond it, and he had never heard anything that scared him so much. It was as though the noises were on his skin and in his ears. Screeks and craaaarks and yowls from wild things all around.

They had wandered around for hours in the day and not found anything that Ben would call food. He had picked grasses, peeled bark and crushed leaves in his fingers – searching and smelling and feeling for things to eat. Not even good things. Just things. He had thought about eating insects and, in the afternoon, he had eyed off the blue-spotted sandwich but it was all too wrong.

They had argued all day about whether to walk up or downstream. Ben had half-hoped that the police helicopter would return. In the end, they had stayed put and as the sun went down they had each filled up on a bellyful of reddish creek water and an unripe fig before snuggling into their tree root home. Ben’s stomach was not fooled.

Now darkness had folded in on them. Ben desperately needed to go to the toilet but he would wait till morning. He had never even been camping before. He imagined the luxury of having a tent, fire, a torch, a sleeping bag, food. He had nothing. Just him, wilderness, Olive, fear. Fear was his fire, keeping him alert and alive. Growing up in a house in the suburbs, right next to a highway, had not prepared him for this. Playing thousands of hours of video games, watching hundreds of movies, playing soccer, helping out in the wrecking yard, watching game shows with Nan – none of it was useful to him now. Someone had pressed ‘reset’ on his life. He had no pantry, no fridge, no shops, no cars, no lights, no bed, no blankets, no roof.

He sat up straight, back against the tree. His bottom was wet and cold. He had large leaves beneath him but they didn’t help. He was gripping a short, thick, heavy branch that he would use as a club if he had to.

‘I’ll go on watch first,’ he had said to Olive. But he knew that he would be on watch second, too. He would stay up all night. Someone had to protect them from animals and insects and strangers and ghosts and police lurking in that fine, silvery moonlight.

Ben had a plan. If anything came for them, he would wake Olive and they would climb the tree. He had worked out the quickest route to the top. Olive was a good tree-climber so she would be okay.

He was glad he wasn’t out there alone. As the hours passed he watched the half-moon crawl slowly across the sky, in and out of the branches of the tree above. Each minute felt like forever. When his head drooped to his chest he pinched and even slapped himself. He focused on the moon. He thought about Pop. When Ben was little he would sit on Nan’s back doorstep and they would look up at the moon and she would tell him that Pop was up there.

‘In the moon?’ Ben would ask.

‘Yep,’ she’d say. ‘Looking down on you. He loved you so much.’

He hoped that Pop was looking down on him now. That someone, somewhere was watching over him. And even though Pop had not met Olive before he died, Ben hoped that he would watch over her too.

He needed a plan.

Something to tell Olive.

To make her think he knew what they should do.

To look like they were in control. Not out.

‘What are we going to do?’ she would say in the morning.

And he would say . . .

Nothing. He would say nothing.

Icy bottom. Freezing fingers. Cold nose. Aching body.

Plan. Why are we running?

He could not remember.

Running because . . . Mum and Dad did the wrong thing. Because of the money. Because of the police. Because the policeman had cut them off, forced them to run downhill to the raft. Then the gunshots. Dead? Maybe. Sometimes he felt certain the shots were for Mum and Dad. Other times he was sure they were okay.

They could run into the wilderness. Go back to the cabin. Try to make it home to Nan. Or tell the police, hand themselves in.

These were Ben’s final thoughts before sleep took him. He did not wake until he heard the footsteps. They were in his dream at first. A man’s feet, in boots, close and staggering through undergrowth. Then vines clutching the man’s legs, tendrils curling around him, trying to stop him. The man breaking the vines.

But when Ben woke he still heard the steps. They were close. He stood, raising the stick. He wanted to wake Olive but he was struck silent by the footsteps.

Ben was sure he was about to die. That this person did not mean good things for him. He ruled out police officers. They don’t work alone and Ben was sure it was just one person. Was it a person? The heaviness of the steps sounded like a man or some large animal. His father? Maybe Dad had come downstream in search of them? Should he say something?

Closer now.

Ben pressed himself back into the roots of the tree and squeezed his club tight, ready to beat whoever or whatever it was over the head, ready to protect Olive. Death could not be worse than this. At home he was scared by his parents arguing after he went to bed, hoping that Dad would not leave. But that did not compare to this feeling now.

Slow steps. Close. Steady. Rustling in between. Dragging. Was it dragging something? Ben strained to see through the black, black night. Too late to wake Olive. Too late to climb the tree. He could not control this. It was not a stop-motion movie. He could only let go, wait, sit with the fear and, when the thing was gone, make a firm promise to himself that he would never sleep again.

‘We shouldn’t be doing this,’ Olive said.

Ben slipped, one foot skidding into the cold creek. He pulled himself up onto the boulder. It was mid-morning, he had his school backpack on and $982,300 in the bag in his hand. He had counted the money at first light. Olive had helped. Ben had decided to tell her everything. She had flipped out, could not believe that Mum would do this. Then she started planning what she would do with the money.

‘We should be going downstream,’ she said.

‘Upstream,’ Ben said.

‘Down.’

‘Up,’ Ben said. ‘Back to the cabin. Back to Nan’s. She’ll know what to do.’

They used the boulders at the edge of the creek as their path, leaping from one to the next.

‘We shouldn’t have left the raft,’ Olive said.

‘Feel free to drag it up the creek if you like.’

Ben had not slept after the thing went by in the night. He still didn’t know who or what it was or if, in that soup of darkness, dream and fear, he had imagined it. In his next life, Ben planned to be brave.

The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.

That line came to him. Who had said that? History teacher. Mr Stone. Silver glasses, wild grey eyebrows.

The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.

Was that true? He wanted to believe it but he wondered if the person who had said it originally had ever been stuck in the wild with snakes and insects and bodies dragging by after midnight.

They had to get back before dark.

‘We’ll get there by dusk,’ he told Olive as they trudged uphill.

‘And what if the police are still there, Mister Sm

artypants?’ Olive asked. She was just ahead of him.

‘Watch out for the mossy rocks.’

‘What if?’ she asked again.

‘We’ll be careful.’

What if Mum and Dad are dead? he wondered. He had not shared his fear with her.

‘I hate Mum and Dad.’

‘Don’t say that.’

‘Well, I do. They wrecked everything.’

‘They’re still our parents.’

Later in the day, when the rocks became steeper and slipperier, they were forced to make a path through thick undergrowth beside the creek. Scratchy lantana bushes with tiny pink, white and yellow flowers grew everywhere. Green-leaved vines twisted through it. Tall palm trees soared upward, searching for light through the canopy.

Upstream.

They had been a day and a half without food. But they would eat tonight. They would make it to the cabin and they would find food there.

‘I can’t go any more,’ Olive said eventually. She stopped and dabbed at the cuts and grazes on her arm. She started to cry. Ben felt like crying too, but he could not. He was the father here and Dad had assured him that real men don’t cry.

‘Don’t be a baby,’ he snapped, pushing on through thick, bristly vines and ferns, blazing a trail. ‘I’ll have to leave you here.’ He felt bad for being so harsh but unless he was tough on himself, tough on Olive, they would not make it back to the cabin before dark.

Listen for the creek, he kept saying to himself. Sometimes it was easier to veer away from the creek but he could not leave it behind.

‘I’m hungry,’ Olive moaned, scrambling to catch up. ‘I want to buy something. We could eat anything in the whole wide world with all that money.’

Ben was bone-hungry. Blood-and-bone-hungry. Mum always told him to eat less, exercise more. ‘You don’t want kids teasing you for being fat,’ she would say when he asked for a sundae at the drive-thru. Mum thought that standing out or being teased were the worst things in the world. Now he was eating less. Eating nothing. He wondered if she would be proud.

‘Do you like Mars Bars or Milky Ways better?’ Olive asked.

On the Run

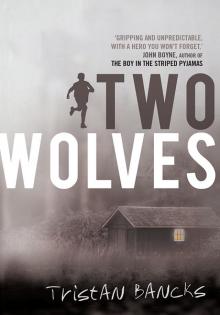

On the Run Two Wolves

Two Wolves Mac Slater Coolhunter 1

Mac Slater Coolhunter 1 The Fall

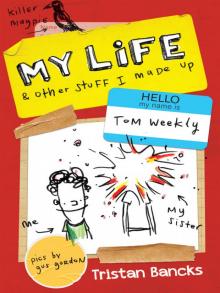

The Fall My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up

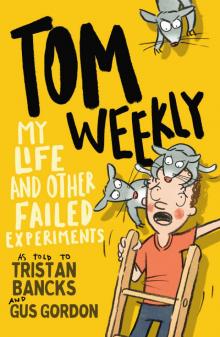

My Life and Other Stuff I Made Up My Life and Other Failed Experiments

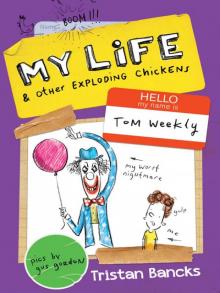

My Life and Other Failed Experiments My Life and Other Exploding Chickens

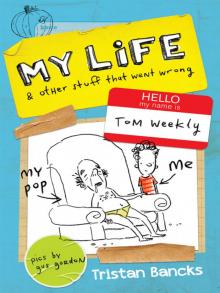

My Life and Other Exploding Chickens My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong

My Life and Other Stuff That Went Wrong Galactic Adventures

Galactic Adventures Mac Slater Coolhunter 2

Mac Slater Coolhunter 2 My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins

My Life and Other Weaponised Muffins